Why does it take so much time to do anything strategic?

This not an uncommon question to hear in technology and, more often than not, the answer is relatively simple: because the focus in the organization is delivering projects and not establishing an environment to facilitate accelerated delivery at scale. Those are two very different things and, unfortunately, it requires more thought, partnership, and collaboration between business and technology teams than headlines like “let’s implement product teams” or “let’s do an Agile transformation” imply. Can those mechanisms be part of how you execute in a scaled environment? Absolutely, but choosing an operating approach and methodology shouldn’t precede or take priority over having a blueprint to begin with, and that’s the focus of this article.

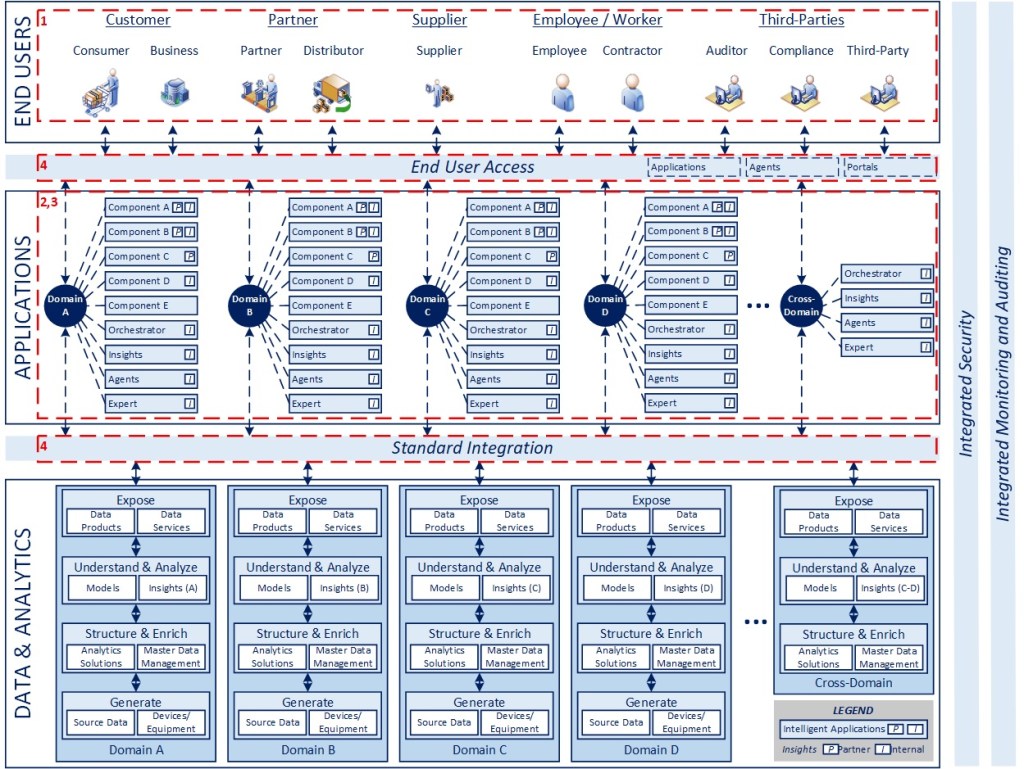

This is the second post in a series focused on where I believe technology is heading, with an eye towards a more harmonious integration and synthesis of applications, AI, and data… what I previously referred to in March of 2022 as “The Intelligent Enterprise”. The sooner we begin to operate off a unified view of how to align, integrate, and leverage these oftentimes disjointed capabilities today, the faster an organization will leapfrog others in their ability to drive sustainable productivity, profitability, and competitive advantage.

Design Dimensions

In line with the blueprint above, articles 2-5 highlight key dimensions of the model in the interest of clarifying various aspects of the conceptual design. I am not planning to delve into specific packages or technologies that can be used to implement these concepts as the best way to do something always evolves in technology, while design patterns tend to last. The highlighted areas and associated numbers on the diagram correspond to the dimensions described below.

User-Centered Design (1)

A firm conducts a research project on behalf of a fast-food chain. There is always a “coffee slick” in the drive thru, where customers stop and pour out part of their beverage. Is there something wrong with the coffee? No. Customers are worried about burning themselves. The employees are constantly overfilling the drink, assuming that they are being generous, but actually creating a safety concern by accident. Customers don’t want to spill their coffee, so that excess immediately goes to waste.

In the world of technology, the idea of putting enabling technology in the hands of “empowered” end users or delivering that one more “game changing” tool or application is tempting, but often doesn’t deliver the value that is originally expected. This can occur for a multitude of reasons, but what can often be the case is an inadequate understanding of the end user’s mental model, approach to performing their work, or a fundamental misunderstanding that more technology in the hands of a user is always a good thing (when it definitely isn’t the case).

Two learnings that came out of the dotcom era were, first, the value to be derived from investing in user-centered design, thinking through their needs and workflow, and designing experiences around that. The other common practice was assuming that a disruptive technology (the internet in this case) was cause to spin out a separate organization (the “eBusiness” teams of the time) meant to incubate and accelerate development of capabilities that embraced the new technology. These teams generally lacked a broader understanding of the “traditional” business and its associated operating requirements, and thus began the ”bricks versus clicks” issues and channel conflict that eventually led to these capabilities being folded back into the broader organization, but only after having spent time and (in many cases) a considerable amount of money experimenting without producing sustainable business value.

In the case of artificial intelligence, it’s tempting to want to stand up new organizations or repurpose existing ones to mobilize the technology or to assume everything will eventually be relegated to a natural language-based interface where a user provides a description of what they want into an agent acting at their personal virtual assistant, with system deriving the appropriate workflow and orchestrating the necessary actions to support the request. While that may be a part of our future reality, taking an approach similar to the dotcom era would be a mistake and there will lost opportunity where this is the chosen path.

To be effective in a future digital world with AI, we need to think of how we want things integrated at the outset, starting with that critical understanding of the end user and how they want to work. Technology is meant to enable and support them, not the other way around, and leading with technology versus a need is never going to be an optimal approach… a lesson we’ve been shown many times over the years, no matter how disruptive the technology advancement has been.

I will address some of the organizational implications of the model in the seventh article in this series, so the remainder of this post will be on the technology framework itself.

Designing Around Connected Ecosystems (2)

Domain-driven design is not a new concept in technology.

As I mentioned in the first article, the technology footprint of most medium- to large-scale organizations is complex and normally steeped in redundancies, varied architectures, unclear boundaries between custom and purchased software, hosted and cloud-based based environments, hard coded integrations, and standard ways of moving data within and across domains.

While package solutions offer some level of logical separation of concerns between different business capabilities, the natural tendency in the product and platform space is to move towards more vertically or horizontally integrated solutions that create customer lock in and make interoperability very challenging, particularly in the ERP space. What also tends to occur is that an organization’s data model is biased to conform to what works best for a package or platform, but not necessarily the best representation of their business or their consumers of technology (something I will address in article 5 on Data & Analytics).

In terms of custom solutions, given they are “home grown”, there is a reasonable probability that, unless they were well-architected at the outset, they very likely provide multiple capabilities, without clear separation of concerns in ways that make them difficult to integrate with other systems in “standard” ways.

While there is nothing unique about these kinds of challenges, the problem comes when new technology capabilities like AI are available and we want to either replace or integrate things in a different way. This is where the lack of enterprise-level design and a broader, component-based architecture takes its toll, because there likely will be significant remediation, refactoring, and modernization required to enable existing systems to interoperate with the new capabilities. These things take time, add risk, and ultimately cost to our ability to respond when these opportunities arise, and no one wants to put new plumbing in a house that is already built with a family living in it.

On the other hand, in an environment with defined, component-based ecosystems that uses standard integration patterns, replacing individual components becomes considerably easier and faster, with much less disruption at both a local- and an enterprise-level. In a well-defined, component-based environment, I should be able to replace my Talent Acquisition application without having to impact my Performance Management, Learning & Development, or Compensation & Benefits solutions from an HR standpoint. Similarly, I shouldn’t need to make changes to my Order Management application within my Sales ecosystem because I’m transitioning to a different CRM package. To the extent that you are using standard business objects to support integration across systems, the need to update downstream systems in other domains should be minimized as well. Said differently, if you want to be fast, be disciplined in your design.

Modular, Composable, Standardized (3)

Beyond designing towards a component-based environment, it is also important to think about capabilities independent of a given process so you have more agility in how you ultimately leverage and integrate different things over time.

Using a simple example from personal lines insurance, I want to be able to support a third-party rating solution by exposing a “GetQuote” function that takes necessary customer information and coverage-related parameters and sends back a price. From a carrier standpoint, the process may involve ordering credit and pulling a DMV report (for accidents and violations) as inputs to the process. I don’t necessarily want these capabilities to be developed internal to the larger “GetQuote”, because I may want to leverage them for any one of a number of other reasons, so that smaller grained (more atomic) transactions should also be defined as services that can be leveraged by the larger one. While this is a fairly trivial case, there are often situations where delivery efforts move at such a rapid pace that things are tightly coupled or built together that really should be discreet and separate, providing more flexibility and leverage of those individual services over time.

This also can occur in the data and analytics space, where there are normally many different tools and platforms between the storage and consumption layers and ideally you want to optimize data movement and computing resources such that only the relevant capabilities are included in a data pipeline based on specific customer needs.

The flexibility described above is predicated on a well-defined architecture that is service-based and composable, with standard integration patterns, that leverages common business objects for as many transactions as practical. That isn’t to say that there are times where the economics make sense to custom code something or to leverage point-to-point integration, rather that thinking about reuse and standardized approaches up front is a good delivery practice to avoid downstream cost and complexity, especially when the rate of new technologies being introduced is as high as it is today.

Leveraging Standard Integration (4)

Having mentioned standard integration above, my underlying assumption is that we’re heading towards a near real-time environment where streaming infrastructure and publish and subscribe models are going to be critical infrastructure to enable delivery of key insights and capabilities to consumers of technology. To the extent that we want that infrastructure to scale and work efficiently and consistently, there is a built-in incentive to be intentional about the data we transmit (whether that is standard business objects or smaller data sets coming from connected equipment and devices) as well as the ways we connect to these pipelines across application and data solutions. Adding a data publisher or consumer shouldn’t require rewriting anything per se, any more than plugging in a new appliance to a power outlet in your home should require you to either unplug something else or change the circuit board and wiring itself (except in extreme cases).

Summing Up

I began this article with the observation about delivering projects by comparison with establishing an environment for delivering repeatably at scale. In my experience, depending on the scale of an organization, there will be some level of many of the things I’ve mentioned above in place, but then a potentially large set of pain points and opportunities across the footprint where things are suboptimized.

This is not about boiling the ocean or suggesting we should start over. The point of starting with the framework itself is to raise awareness that the way we establish the overall environment has a significant ripple effect into our ability to do things we want to do downstream to leverage new capabilities and get the most out of our technology investments later on. The time spent in design is well worth the investment, so long as it doesn’t become analysis paralysis.

To that end, in summary:

- Design from the end user and their needs first

- Think and design with connected ecosystems in mind

- Be purposeful in how you design and layer services to promote reuse and composability

- Leverage standards in how you integrate solutions to enable near real-time processing

It is important to note that, while there are important considerations in terms of hosting, security, and data movement across platforms, I’m focusing largely on the organization and integration of the portfolios needed to support an organization. From a physical standpoint, the conceptual diagram isn’t meant to suggest that any or all of these components or connected ecosystems need to be managed and/or hosted internal to an organization. My overall belief is that, the more we move to a service-driven environment, the more of a producer/consumer model will emerge where corporations largely act as an integrator and orchestrator (aka “consumer”) of services provided by third-parties (the “producers”). To the extent that the architecture and standards referenced above are in place, there shouldn’t be any significant barriers to moving from a more insourced and hosted environment to a more consumption-based, outsourced, and cloud-native environment in the future.

With the overall framework in place, the next three articles will focus on the individual elements of the environment of the future, in terms of AI, applications, and data.

Up Next: Integrating Artificial Intelligence

I hope the ideas were worth considering. Thanks for spending the time to read them. Feedback is welcome as always.

-CJG 07/26/2025

One thought on “The Intelligent Enterprise 2.0 – A Framework for the Future”