What It Is: Governance (in a delivery context) is the process for reviewing a portfolio of ongoing work in the interest of enabling risk management, containing avoidable cost, and increasing on-time delivery. PMOs (Project/Program Management Offices) are the mechanism through which governance is typically implemented in many organizations.Why It Matters: As the volume, risk, and complexity in a portfolio increase, there is typically a disproportionate increase in issues that come about, leading to cost overruns, missed expectations on scope or schedule (or both), and reduced productivity. PMOs, meant to be a mechanism to mitigate these issues, are often set up or executed poorly, becoming largely administrative and not value-generating capabilities, which furthers or amplifies any underlying execution issues. In an environment where organizations want to transform while managing a high level of value/cost efficiency, a disciplined and effective governance environment is critical to promoting IT excellence

Key Concepts

- There are countless ways to set up an operating model in relation to PMOs and governance, but the culture and intent have to be right, or the rest of what follows will be more difficult

- There is a significant difference between a “governing” and an “enabling” PMO in how people perceive the capability itself. While PMOs are meant to accomplish both ends, the priority is enabling successful, on-time, quality delivery, not establishing a “police state”

- Where the focus of a PMO becomes “governance” that doesn’t drive engagement and risk management it can easily become an administrative entity that drives cost and doesn’t create value and ultimately undermines the credibility of the work as a whole

- The structure of the overall operating model should align to the portfolio of work, scale of the organization, and alignment of customers to ongoing projects and programs

- It can easily be the case that the execution of the governance model can adapt and change year-over-year but, if designed properly, the structure and infrastructure should be leverageable, regardless of those adjustments

- The remainder of this article with introduce a concept for how to think about portfolio composition and then various dimensions to consider in creating an operating model for governance

Framing the Portfolio

In chalking out an approach to this article, I had to consider how to frame the problem in a way that could account for the different ways that IT portfolios are constructed. Certainly, the makeup of work in a small- to medium-size organization is vastly different than a global, diversified organization. It would also be different when there are a large number of “enterprise” projects versus a set of highly siloed, customer-specific efforts. To that end, I’m going to introduce a way of thinking about the types of projects that typically make up an IT project portfolio, then an example governance model, the dimensions of which will be discussed in the next section.

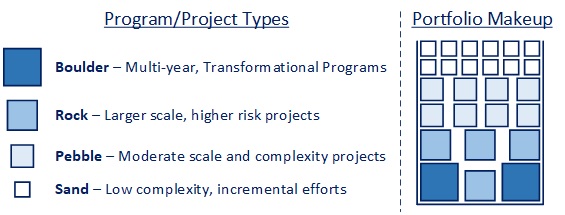

The above graphic provides a conceptual way to organize delivery efforts, using the rocks, pebbles, and sand in a jar metaphor that is relatively well known, and also happens to apply to organizing technology delivery.

To establish effective governance, you generally first want to examine and classify delivery projects/programs based on scale (in effort and budget), risk, timeframe, and so on. This is important so as not to apply a “one size fits all” approach to how you track and govern projects that encumbers lower complexity efforts with the same level of reporting that you would typically have on larger-scale, transformation programs.

In the model above, I went with a simple structure of four project types:

- Sand – very low risk projects that can be something like a rate change in Insurance or data change in analytics

- Pebbles – medium complexity work like incremental enhancements or an Agile sprint

- Rocks – something material, like a package implementation, new technology introduction, product upgrade, or new business or technology capability delivery

- Boulders – high complexity, multi-year transformation programs, like an ERP implementation where there are multiple material, related projects under one larger delivery umbrella

The characteristics of these projects and metrics you would ideally like to gather, along with the level of “review” needed on an ongoing basis would vary greatly, which will be explored in the next section.

In a real-world scenario, it is possible that you might want to identify additional sub-categories to the degree it helps inform architecture or delivery governance processes (e.g., security, compliance, modernization, AI-related projects), most of which would likely be specialized kinds of “Pebbles” and “Rocks” in the above model. It is very easy to become bloated quickly in terms of a governance process, so I am generally a proponent of tuning the model to the work and asking only questions relevant to the type of project being discussed.

What about Agile/SAFe and Product team-oriented environments? In my experience, it is beneficial to segment delivery efforts because, even in product-based environments, there are normally a mix of projects that are more monolithic in nature (i.e., that would align to “Rocks” and “Boulders”). Sprints within iterative projects (for a given product team) would likely align to “Pebbles” in the above model and the question would be how to align the outcome of retrospectives into the overall governance model, which will be addressed below.

So, coming back to the diagram, for the purposes of illustration, the assumption we will use is that the portfolio we’re supporting is a mix of all four project types (the “Portfolio Makeup” at right above), so that we can discuss how the governance can be layered and integrated across the different categories expressed in the model itself.

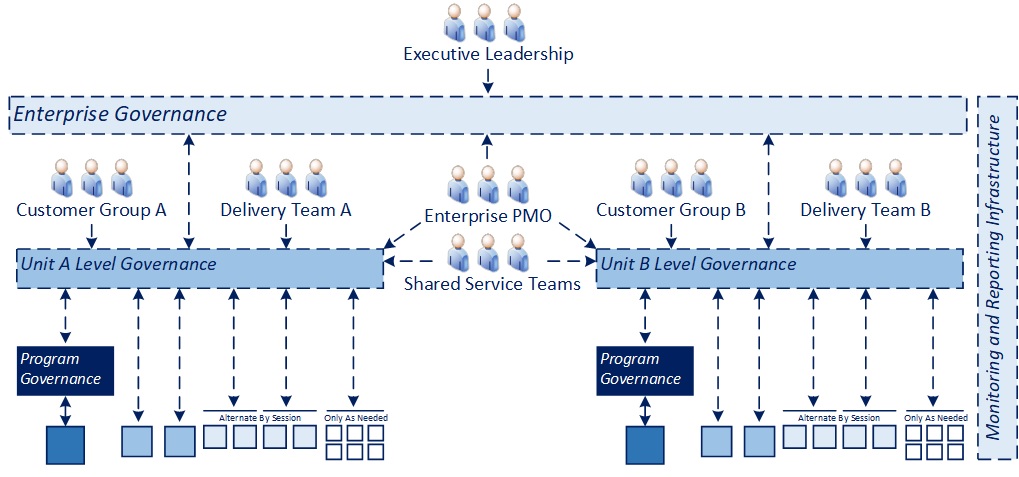

For the remainder of this article, we will assume the work in the delivery portfolio is divided equally between two business customer groups (A and B), with delivery teams supporting each as represented in the below diagram.

If your individual scenario involved a common customer, the model below could be simplified to one branch of the two represented. If there were multiple groups, it could be scaled horizontally (adding branches for each additional organization) or if there were multiple groups across various geographies, it could be scaled by replicating and sizing the entire structure by entity (e.g., work organized by country in a global organization or by operating company in a conglomerate with multiple OpCos) and then adding one additional later for enterprise or global governance.

Key Dimensions

There are many dimensions to consider in establishing an enterprise delivery governance model. The following breakdown is not intended to be exhaustive, but rather to highlight some key concepts that I believe are important to consider when designing the operating model for an IT organization.

General Design Principles

- The goal is to enable decisions as close to the delivery as possible to improve efficiency and minimize the amount of “intervention” needed, unless it is a matter of securing additional resources (labor, funding, etc.) or addressing change control issues

- The model should leverage a common operating infrastructure to the extent possible, to enable transparency and benchmarking across projects and portfolios. The more consistency and the more “plug and play” the infrastructure for monitoring and governance is, the faster (and more cost-effectively) projects and programs can typically be kicked off and accelerated into execution without having to define these processes independently

- Metrics should move from summarized to more detailed as you move from oversight to execution, but the ability to “’drill down” should ideally be supported, so there is traceability

Business and IT PMOs versus “One” consolidated model

- There is a proverbial question as to whether it is better to have “one”, integrated PMO construct, or an IT PMO separate from one that manages business dependencies (whether centralized or distributed)

- From my perspective, this is a matter of scale and complexity. For smaller organizations, it may be efficient and practical to run everything through the same process, but as work scales, my inclination would be to separate concerns to keep the process from becoming too cumbersome and leverage the issue and risk management infrastructure to track and manage items relevant to the technology aspects of delivery. There should be linkage and coordination to the extent that parallel organizations exist, but I would generally operate them independently so they can focus on their scope of concerns and be as effective as possible

Portfolio Management Integration

- I’m assuming that portfolio management processes would operate “upstream” of the governance process and inform which projects are being slotted, address overall resource management and utilization, and release strategy

- To the extent that change control in the course of delivery affects a planned release, a reverse dependency exists from the governance process back to the portfolio management process to see if schedule changes necessitate any bumping or reprioritization because of resource contention or deployment issues

IT Operations Integration

- The infrastructure used to track and monitor delivery should come via the IT Operations capability, theoretically connecting at the IT Scorecard for executive level delivery metrics to portfolio and project metrics tracked at the execution level

- IT Operations should own (or minimally help establish) the standards for reporting across the entire operating model

Participation

- IT Operations should facilitate centralized governance processes as represented in the “Unit-level” and “Enterprise” governance processes in the diagram above. Program-level governance for “Boulders” would likely be best run by the delivery leadership accountable for those efforts

- Participation should include whoever is needed to engage and resolve 80% (anecdotally) of the issues and risks that could be raised, but be limited to only people who need to be there

- Governance processes should never be a “visibility” or “me too” exercise, they are a risk management and issue resolution activity, meant to drive engagement and support for delivery. Notes and decisions can and should be distributed to a broader audience as appropriate so additional stakeholders are informed

- In the context of a RACI model (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed), meetings should include only “R” and “A” parties, who can reach out to extended stakeholders as needed (“C”), but very rarely anyone who would be defined as an “I” only

- It is very easy to either overload a meeting to the point it becomes ineffective or not include the right participants to the extent it doesn’t accomplish anything, so this is a critical consideration for making a governance model effective

Session Scope and Scheduling

- I’ve already addressed participation, but scheduling should consider the pace and criticality of interventions. Said differently, a frequent, recurring process may make sense when there is a significant volume of work, but something more episodic if there are a limited number of major milestones over the course of time where it makes sense to review progress and check in at specific points in time

- Where an ongoing process is intended, “Boulders” and “Rocks” should have a standing spot on the agenda given the criticality and risk profiles of those efforts likely would be high. For “Pebbles”, some form of rotational involvement might make sense, such as including two of the four projects in the example above in every other meeting, or prioritizing any projects that are showing a Yellow or Red overall project health. In the case of the “Sand”, those projects likely are so low risk that, beyond reporting some very basic operating metrics, they should only be included in a governance process when there is an issue that requires intervention or a schedule change that involves potential downstream impacts

Governance Processes

- I mentioned this in concert with the example portfolio structure above, but it is important to consider tailoring the governance approach to the type of work so as not to create a cumbersome or bureaucratic environment for delivery teams where they focus on reporting and not managing and delivering their work

- Compliance and security projects, as an example, are different than AI, modernization, or other types of efforts and should be reviewed with that in mind. To the extent a team is asked to provide a set of information as input to a governance process that doesn’t align cleanly to what they are doing, it becomes a distraction that creates no value. That being said, there should be some core indicators and metrics that are collected regardless of the project type and reviewed consistently (as will be discussed in the next dimension)

- The process should be designed and managed by IT Operations so it can be leveraged across an organization. While individual nuances can be applied that are specific to a particular delivery organization, it is important to have consistency to enable enterprise-level benchmarking and avoid the potential biases that can come from teams defining their own standards that could limit transparency and hinder effective risk management

Delivery Health and Metrics

- I’ve written separately on Health and Transparency, but minimally every project should maintain a Red, Yellow, Green on Overall Health, and a second-level indicator on Schedule, Scope, Cost, Quality, and Resourcing that a project/program manager could supply very easily on an ongoing basis. That data should be collected at a defined interval to enable monitoring and inform governance processes on an ongoing basis, regardless of other quantitative metrics gather

- Metrics on financials, resourcing, quality, issues, risks, and schedule can vary, but to the extent they can be drawn automatically from defined system(s) of record (e.g., MS Project, financial systems, a time tracking system with defined project coding, defect or incident management tools), the level of manual intervention required to enable governance should ideally be limited to data teams should be utilizing on an ongoing basis

- In the event that there are multiple systems in place to track ongoing work, the IT Operations team should work with the delivery stakeholders to identify any enterprise-levels standards required to normalize them for reporting and governance purposes. To give a specific example, I encountered a situation once where there were five different defect management systems in place across a highly diversified IT organization. In that case, the team developed a standard definition of how defects would be tracked and reported and the individual systems of record were mapped to that definition so that reporting was consistent across the organization

Change Control

- Change is a critical area to monitor in any governance process because of the potential impact it has to resource consumption (labor, financials), customer delivery commitments, and schedule conflicts with other initiatives

- Ideally a governance process should have the right information available to understand the implications of change as and when it is being reviewed as well as the right stakeholders present to make decisions with that information having been provided

- To the extent that schedule, financial, or resource considerations change, information would need to be sent back to the IT Portfolio Management process to remedy any potential issues or disruptions that have been caused through decisions made. This is consistently missed in my experience in large delivery portfolios

Issue and Risk Management

- Leveraging a common issue and risk management infrastructure both promotes a consistent way to track and report on these things across delivery efforts, but also creates a repository of “learnings” that could be reviewed and harvested in the interest of evaluating the efficacy of different approaches taken for similar issues/risks and promoting delivery health over time

Dependency/Integrated Plan Management

- There are two dimensions to consider when it comes to dependencies. First is whether they exist within a project/program or are a dependency from that effort to others in the portfolio or downstream of it. Second is whether the dependency is during the course of effort or connected to the delivery/deployment of the project

- In my experience, teams are very good at covering project- or program-driven dependencies, but there can be major gaps in looking across delivery efforts to account for risks caused when things change. To that end, some level of dependency-related matrix should exist to identify and track dependencies across delivery efforts separate from a release calendar that focuses solely on deployment and “T-minus” milestones as projects near deployment

- Once these dependencies are being tracked, changes that surface through the governance process can be escalated back to the IT Portfolio Management process and other delivery teams to understand and coordinate any adjustments required

- This can include situations where there are sequential dependencies, as an example, where a schedule overrun requires additional resource commitment from a critical resource needed to kick off or participate in another delivery effort. Without a means to identify these dependencies, the downstream effort may be delayed or not have time to explore alternate resourcing options without having a ripple effect to that downstream delivery. This is part of the argument for leveraging named resource planning (versus exclusively FTE-/role-based) for critical resources when slotting during the portfolio management process

Partner/Vendor Management

- The IT Operations function should ideally help ensure that partners leverage internal reporting mechanisms or minimally conform to reporting standards and plug into existing governance processes where appropriate to do so

- In the case of “Rocks” and “Boulders” that are largely partner-driven they likely will have a standalone governance process that leverages whatever process the partner has in place, but the goal should be to integrate and leverage whatever enterprise tools and standards are in place so that work can be benchmarked across delivery partners and also to compare the service delivery to internally-led efforts as well

- It is very tempting to treat sourced work differently than projects delivered internal to IT, but who delivers a project should be secondary to whether the project is delivered on time, with quality and meets its objectives. The standards of excellence should apply regardless of who does the work

Learnings and Best Practices

- Part of the potential benefit for having a shared infrastructure for executing governance discussions by comparison with distributing the work is that it enables you to see patterns in delivery, consistent bottlenecks, risks, and delays, and to leverage those learnings over time to improve delivery quality and predictability

- Part of the governance process itself can also include having teams provide a post-mortem on their delivery efforts upon completion (successful or otherwise) so that other teams that participate in the governance process and the broader governance team can leverage those insights as appropriate

Change Management

- While change management isn’t an explicit focus of a PMO/governance model, the dependency management surrounding deployment and learnings coming from various deployments should be coordinated with larger change management efforts and inform them on an ongoing basis in the interest of promoting more effective integration of new capabilities

Some Notes on Product Teams/Agile/SAFe Integration

- It is tempting to treat product teams as isolated, independent, and discrete pieces of delivery. The issue with moving fully to that concept is that it becomes easy to lose transparency and benchmarking across delivery efforts that surface opportunities to more effectively manage risks and issues outside a given product/delivery team

- To that end, part of the design process for the overall governance model should look at how to leverage and/or integrate the tooling for Agile projects with other enterprise project tracking tools as needed, along with integrating learnings from retrospectives with overall delivery improvement processes

Wrapping Up

Overall, there are many considerations that go into establishing an operating model for PMOs and delivery governance at end enterprise level. The most important takeaway is to be deliberate and intentional about what you put in place, keep it light, do everything you can to leverage data that is already available, and keep the balance between the project and the portfolio in mind at all times. The more project-centric you become, the more likely you will end up siloed and inefficient overall, and that will translate into missed dates, increased costs, and wasted utilization.

For Additional Information: On Health and Transparency, On Delivering at Speed, Making Governance Work, InBrief: IT Operations

Excellence doesn’t happen by accident. Courageous leadership is essential.

Put value creation first, be disciplined, but nimble.

Want to discuss more? Please send me a message. I’m happy to explore with you.

-CJG 12/19/2025