Ok, I have the scope identified, but what do I do now?

Having recently written about the intangibles and scope associated with simplification, the focus of this article is the process of rationalization itself, with an eye towards reducing complexity and operating cost.

The next sections will breakdown the steps in the process flow above, highlighting various dimensions and potential issues that can occur throughout a rationalization effort. I will focus primarily on the first three steps (i.e., the analysis and solutioning), given that is where the bulk of the work occurs. The last two steps are largely dedicated to socializing and executing on the plan, which is more standard delivery and governance work. I will then provide a conceptual manufacturing technology example to illustrate some ways the exercise could play out in a more tangible way.

Understand

The first step of the process is about getting a thorough understanding of the footprint in place to enable reasonable analysis and solutioning. This does not need to be exhaustive and can be prioritized based on the scope and complexity of the environment.

Clarify Ownership

What’s Involved:

- Identifying technology owners of sets of applications, however they are organized. Hereinafter referred to as portfolio owners

- Identifying primary business customers for those applications (business owners)

- Identifying specific individuals who have responsibility for each application (application owners)

- Portfolio and application owners can be the same individual, but in larger organizations, they likely won’t be given the scope of an individual portfolio and ways it is managed

Why It Matters:

- Subject matter knowledge will be needed relative to applications and the portfolios in which they are organized, the value they provide, their alignment to business needs, etc.

- Opportunities will need to be discussed and decisions made related to ongoing work and the future of the footprint, which will require involvement of these stakeholders over time

Key Considerations:

- Depending on the size of the organization and scope of various portfolios in place, it may be difficult to engage the right leaders in the process, in which case a designate should be identified who can serve as a day-to-day representative of a larger organization, who is empowered to provide input and make recommendations on behalf of their respective area.

- In these cases, a separate process step will need to be added to socialize and confirm the outcomes of the process with the ultimate owners of the applications to ensure alignment, regardless of the designated responsibilities of the people participating in the process itself. Given the criticality of simplification work, there could be substantial risk in making broad assumptions related to organizational support and alignment, so some form of additional checkpoints would be a good idea in nearly all cases where this occurs

Inventory Applications

What’s Involved:

- Working with Portfolio Owners to identify the assets across the organization and create as much transparency as possible into the current state environment

Why It Matters:

- There are two things that should come from this activity: an improved understanding of what is in place, and an intangible understanding of the volatility, variability, and level of opacity in the environment itself. In the case of the latter point, if I find that I have a substantial amount more applications across a set of facilities or set of operating units than I expected and those vary by business greatly, it should inform how I think about the future state environment and governance model I want in place to manage that proliferation in the future. This is related to my point on being a “historian” in the process in the previous article on managing the intangibles of the process.

Key Considerations:

- Catalogue the unique applications in production, providing a general description of what they do, users of the technology (business units, individual facilities, customer segments/groups), primary business function(s)/capabilities provided, criticality of the solution (e.g., whether it is a mission-critical/“core” or supporting/”fringe” application), teams that support the application, number of application instances (see the next point), key owners (in line with the roles mentioned above), mapping to financials (the next point after this), mapping to ongoing delivery efforts (also described below), and any other critical considerations where appropriate (e.g., on a technology platform that is near end of life)

- In concert with the above, identify the number of application instances in production, specifically the number of different configurations of a base application running on separate infrastructure, supporting various operations or facilities with unique rules and processes, or anything that would be akin to a “copy-paste-modify” version of a production application. This is critical to understand and differentiate, because the simplification process needs to consider reducing these instance counts in the interest of streamlining the future state. That simplification effort can be a separate and time-consuming activity on top of reducing the number of unique applications as a whole

- Whether to include hosting and the technology stack of a given application is a key consideration in the inventory process itself. In general, I would try to avoid going too deep, too early in the rationalization process, because these kinds of issues will surface during the analysis effort anyway and putting them in the first step of the process could slow down the work documenting things on applications that aren’t ultimately the top priority for simplification

Understand Financials

What’s Involved:

- Providing a directionally accurate understanding of direct and indirect cost to individual applications across the portfolio

- Providing a lens on the expected cost of any discretionary projects targeted at enhancing replacing, or modernizing individual applications (to the extent there is work identified)

Why It Matters:

- Simplification is done primarily to save or redistribute cost and accelerate delivery and innovation. If you don’t understand the cost associated with your footprint, it will be difficult to impossible to size the relative benefit of different changes you might make and, as such, the financial model is fundamental to the eventual business case meant to come as an output of the exercise

Key Considerations:

- Direct cost related to dedicated teams, licensing, and hosted solutions can be relatively straightforward and easy to gather, along with the estimated cost of any planned initiatives for a specific application

- Direct cost can be more difficult to ascertain when a team or third-party supports a set of applications, in which case some form of cost apportionment may be needed to estimate individual application costs (e.g., allocate cost based on number of production tickets closed by application within a portfolio of systems)

- Indirect expenses related to infrastructure and security in particular can be difficult to understand depending on the hosting model (e.g., dedicated versus shared EC2 instances in the cloud versus on premises, managed hardware) and how costs for hardware, network, cyber security tools, and other shared services are allocated and tracked back to the portfolio

- As I mentioned in my article on the intangibles associated with rationalization, directional accuracy is more important than precision in this activity, because the goal at the early stage of the process is to identify redundancies where there is material cost savings potential, not building out a precise cost allocation for infrastructure in the current state

Evaluate Cloud Strategy

What’s Involved:

- Clarifying the intended direction in terms of enterprise hosting and the cloud overall, along with the approach being taken where cloud migration is in progress or planned at some level moving forward

Why It Matters:

- Hosting costs change when moving from a hosted to a cloud-based environment, which could affect the ultimate business case, depending on the level of change planned in the footprint (and associated hosting assumptions)

Key Considerations:

- There is a major difference in costs for hosting depending on whether you are planning to use a lift-and-shift, modernize, or “containerize”-type of approach to the cloud,

- Not all applications will be suitable to the last approach in particular, and it’s important to understand whether this will play into your application strategy as you are evaluating the portfolio and identifying future alternatives

- If there is no major shift planned (e.g., because the footprint is already cloud-hosted and modernized or containerized), it could be that this is a non-issue, but likely it does need to be considered somewhere in the process, minimally from a risk management and business case development standpoint

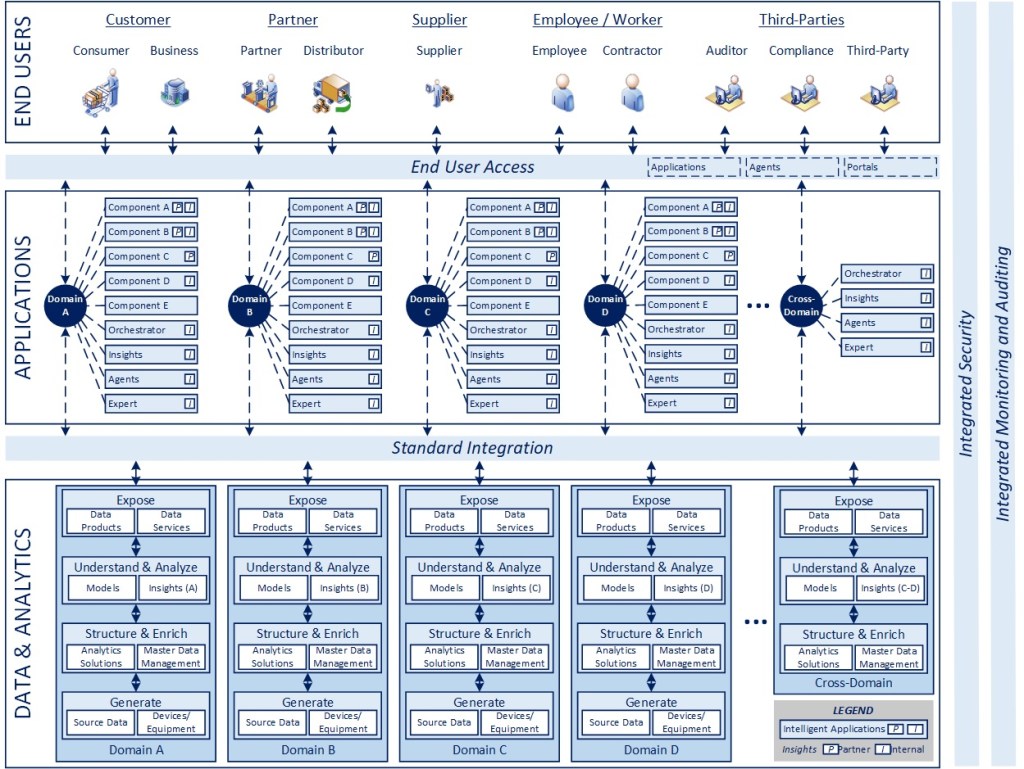

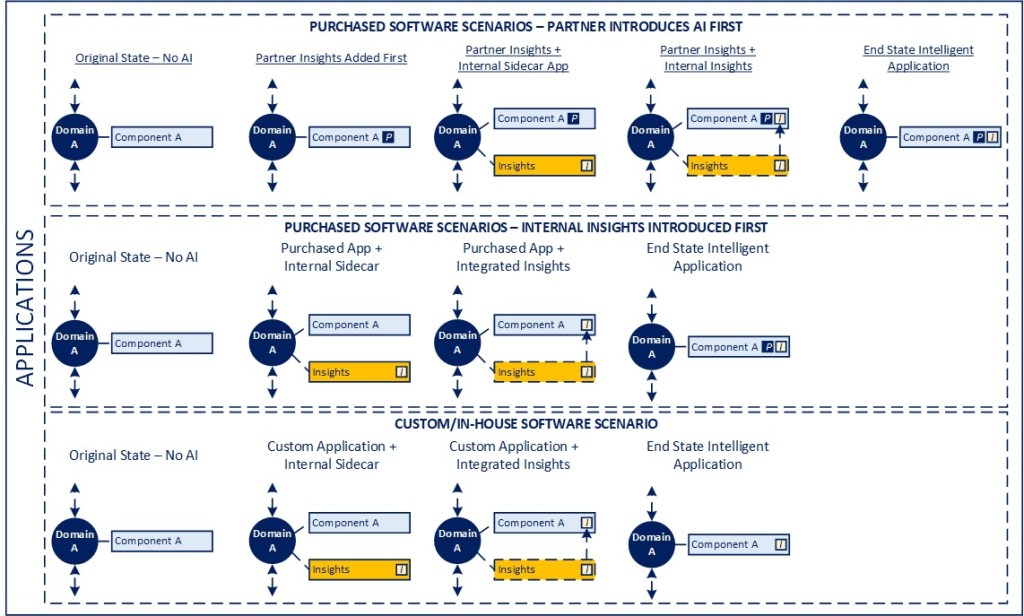

Evaluate AI Strategy

What’s Involved:

- Understanding the role AI applications and agentic AI solutions are meant to be a core component in the future application portfolio and enterprise footprint, along with any primary touchpoints for these capabilities as appropriate

- Understanding any high opportunity areas from an end user standpoint where AI could aid in improving productivity and effectiveness

Why It Matters:

- Any longer-term strategy for enterprise technology today needs to contemplate and articulate how AI is meant to integrate and align to what is going to be in place, particularly if agentic AI is meant to be included as part of the future state, otherwise you risk having to iterate your entire blueprint relatively quickly, which could lead to issues in stakeholder confidence and momentum

Key Considerations:

- If Agentic AI is meant to be a material component in the future state, the evaluation process for targeted applications should include their API model and whether they are effectively “open” platforms that can be orchestrated and remote operated as part of an agentic flow. The larger the overall scope of the strategy and longer the implementation is expected to take, the more important this aspect should be as a consideration in the analysis process itself, because orchestration is going to become more critical in large enterprises over time under almost any circumstances

- Understanding the role AI is anticipated to play is also important to the extent that it could play a critical role in facilitating transition in the implementation process itself, particularly if it becomes an integrated part of the end user presentment or education and training environment. This could both help reduce implementation costs and accelerate deployment and adoption, depending on how AI is (or isn’t leveraged)

Assess Ongoing Work

What’s Involved:

- The final aspect to understanding the current state is obtaining a snapshot of the ongoing delivery portfolio and upcoming pipeline

Why It Matters:

- Understanding anticipated changes, enhancements, replacements, or retirements and the associated investments is important to evaluating volatility and also determining the financial consequences of decisions made as part of the strategy

Key Considerations:

- Gather a list of active and upcoming projects, applications in scope, the scope of work, business criticality, any significant associated risk, relative cost, and anticipated benefits

- Review the list with owners identified in the initial step with a mindset of “go”, “stop”, and “pause” given the desire to simplify overall. It may be the case that some inflight work needs to be completed and handled as sunk cost, but there could be cost avoidance opportunity early on that can help fund more beneficial changes that improve the health of the footprint overall

Evaluate

With a firm understanding of the environment and a chosen set of applications to be explored further (which could be everything), the process pivots to assessing what is in place and identifying opportunities to simplify.

Assess Portfolio Quality

What’s Involved:

- Work with business, portfolio, and application owners to apply a methodology, like Gartner’s TIME model, to evaluate the quality of solutions in place. In general, this would involve looking at both business and technology fit in the interest of differentiating what does and doesn’t work, what needs to change, and what requirements are critical to the future state

Why It Matters:

- Rationalization efforts can be conducted over the course of months or weeks, depending on the scope and goals of the activity. Consequently, the level of detail that can be considered in the analysis will change based on the time and resources available to support the effort but, regardless of the time and effort available, it is important for there to be a fact-based foundation to support the opportunities identified, even if only at an anecdotal level

Key Considerations:

- There are generally two levels of this kind of analysis: a higher-level activity like the TIME model, which provides more of a directional perspective on the underlying applications and a more detailed gap analysis-type activity that evaluates features and functionality in the interest of vetting alternatives and identifying gaps that may need to be addressed in the rationalization process itself. The more detailed activity would typically be performed as part of an implementation process and not upstream in the strategy definition phase. The gap analysis could be performed leveraging a standard package evaluation process (replacing external packages with the applications in place), assuming one exists within the organization

- The technical criteria for the TIME model evaluation should include things like AI readiness, platform strategy, underlying technical stack, and other key dimensions based on how critical those individual elements are, as surfaced during the initial stage of the work

Identify Redundancies

What’s Involved:

- Assuming some level of functional categories and application descriptions were identified during the data gathering phase of the work, it should be relatively straightforward to identify potential redundancies that exist in the environment

Why It Matters:

- Redundancies create opportunities for simplification, but also for improved capabilities. The simplification process doesn’t necessarily mean that those having an application replaced will be “giving up” existing capabilities. It could be the case that the solution to which a given user group is being migrated provides more capabilities than what they currently have in place

Key Considerations:

- Not all groups within a large organization have equal means to invest in systems capabilities. There can be situations where migrating smaller entities to solutions in use by larger and more well-funded pieces of the organization allows them to leverage new functionality not available in what they have

- In the situation where organizations move from independent to shared/leveraged solutions, it is important to not only consider how the shift will affect cost allocation, but also the prioritization and management of those platforms post-implementation. A concern can often arise in these scenarios that either costs will be apportioned in a way that burdens smaller entities at a greater level of funding than they can sustain or that their needs may not be prioritized effectively once they are in a shared environment with other. Working through these mechanics is a critical aspect of making simplification work at an enterprise level. There needs to be a win-win environment to the maximum extent possible or it will be difficult to incent teams to move in a more common direction

Surface Opportunities

What’s Involved:

- With redundancies identified, costs aligned, and some level of application quality/fit understood, it should be possible to look for opportunities to replace and retire solutions that either aren’t in use/creating value or that don’t provide the same level of capability in relation to cost as others in the environment

Why It Matters:

- The goal of rationalization is to reduce complexity and cost while making it easier and faster to deliver capabilities moving forward. Where cost is consumed in maintaining solutions that are redundant or that don’t create value, they hamper efforts to innovate and create competitive advantage, which is the overall goal of this kind of effort

Key Considerations:

- Generally speaking, the opportunities to simplify will be identified at a high-level during the analysis phase of a rationalization effort. The detailed/feature-level analysis of individual solutions is an important thing to include in the planning of subsequent design and implementation work to surface critical gaps, integration points, and workflow dependencies between systems to facilitate transition to the desired future state environment

Strategize

Having completed the Analysis effort and surfaced opportunities to simplify the footprint, the process shifts to identifying the target future state environment and mapping out the approach to transition.

Define Future Blueprint(s)

What’s Involved:

- Assuming some representation of the current state environment has been created as a byproduct of the first two steps of the process, the goal of this activity is to define the conceptual end state footprint for the organization

- To the extent that there are corporate shared services, multiple business/commercial entities, operating units, facilities, locations, etc. to be considered, the blueprint should show the simplified application landscape post-transition, organized by operating entity, where one or more operating unit could be mapped into a common element of the future blueprint (e.g., organized by facility type versus individual locations, lower complexity business units versus larger entities)

Why It Matters:

- A relatively clear, conceptual representation of the future state environment is needed to facilitate discussion and understanding of the difference between the current environment, the intended future state, and the value for changes being proposed

Key Considerations:

- Depending on the breadth and depth of the organization itself, the representation of the blueprint may need to be defined at multiple levels

- The approach to organizing the blueprint itself could also provide insight into how the implementation approach and roadmap is constructed, as well as how stakeholders are identified and aligned to those efforts

Map Solutions

What’s Involved:

- With opportunities identified and a future state operating blueprint, the next step is to map retained solutions into the future state blueprint and project the future run rate of the application footprint

Why It Matters:

- The output of this activity will both provide a vision of the end state and act as input to socializing the vision and approach with key stakeholder in the interest of moving the effort forward

Key Considerations:

- There is a bit of art and science when it comes to rationalization, because too much standardization could limit agility if not managed in a thoughtful. I will provide an example of this in the scenario following the process, but a simple example is to think about whether maintaining separate instances of a core application is appropriate in situations where speed to market or individual operating units need the flexibility to have greater autonomy than they might otherwise have if they had to operate off a single, shared instance of one application

- I mentioned in the article on the intangibles of simplification, that is it a good idea to take an aggressive approach to the future state, because likely not everything will work in practice and the entire goal of the exercise is to try and optimize as much as possible in terms of value in relation to cost

- From a financial standpoint, it is important to be conservative in assumptions related to changes in operating expense. That should manifest itself in allowing for contingency in implementation schedule and costs as well as assuming the decommissioning of solutions will take longer than expected (it most likely will). It is far better to be ahead of a conservative plan than to be perpetually behind an overly aggressive one

Define Change Strategy

What’s Involved:

- With the current and future blueprints identified, the next step would be to identify the “building blocks” (in conceptual terms) of the eventual roadmap. This is essentially a combination of three things: application instances to be consolidated, replacement of one application by another, and retirement of applications that are either unused or that don’t create enough value to continue supporting them

- Opportunities can also be segregated into big bets that affect core systems and material cost/change, those that are more operational and less substantial in nature, and those that are essentially cleanup of what exists. The segregation of opportunities can help inform the ultimate roadmap to be created, the governance model established, and program management approach to delivery (e.g., how different workstreams are organized and managed)

Why It Matters:

- Roadmaps are generally fluid beyond a near-term window because things inevitably occur during implementation and business priorities change. Given there can be a lot of socializing of a roadmap and iteration involved in strategic planning, I believe it’s a good idea to separate the individual transitions from the overall roadmap itself, which can be composed in various ways, depending on how you ultimately want to tackle the strategy. At a conceptual level, you can think of it as a set of Post-it notes representing individual efforts that can be organized in a number of legitimate ways with different cost, benefit, and risk profiles

Key Considerations:

- Individual transitions can be assessed in terms of risk, business implications, priority, relative cost and benefits, and so forth as a means to help determine slotting in the overall roadmap for implementation

Develop Roadmap

What’s Involved:

- With the individual building blocks for transition identified, the final step in the strategy definition stage is to develop one or more roadmaps to assemble those blocks to explore as many implementation strategies as appropriate

Why It Matters:

- The roadmap is a critical artifact in the formation of an implementation plan, though they generally change quite a bit over time depending on the time horizon, scope, complexity, and scale of the program itself

Key Considerations:

- Ensure that all work is included and represented, including any foundational or kickoff-related activities that will serve the program as a whole (e.g., establishing a governance model, PMO, etc.)

- Include retirements (not just new solution deployments), minimally as milestones, in the roadmap so they are planned and accounted for. There are many times this is missed in my experience with new system deployments

- Depending on the scale of implementation, explore various business scenarios (e.g., low risk work up front, big bets first, balanced approaches, etc.) to ascertain the relative cost, benefit, implementation requirements, and risks of each and determine the “best case” scenario to be socialized

Socialize and Mobilize

Important footnote: I’ve generally assumed that the process above would be IT-led with a level of ongoing business participation given much of the data gathering and analysis can be performed within IT itself. That isn’t to say that solutioning and development of a roadmap needs to be created and socialized in a sequential manner as is outlined here. It could also be the case that opportunities are surfaced out of the evaluation effort and then the strategy and socialization is done through a collaborative/ workshop process, it depends on the scope of the exercise and nature of the organization.

With the alternatives and future state recommendations prepared, the remaining steps of the process are fairly standard, in terms of socializing and iterating the vision and roadmap, establishing a governance model and launching the work with clear goals for 30, 60, and 90 days in mind. As part of the ongoing governance process, it is assumed that some level of iteration of the overall roadmap and goals will be performed based on learnings gathered early in the implementation process.

Putting Ideas into Practice – An Example

The Conceptual Example – Manufacturing

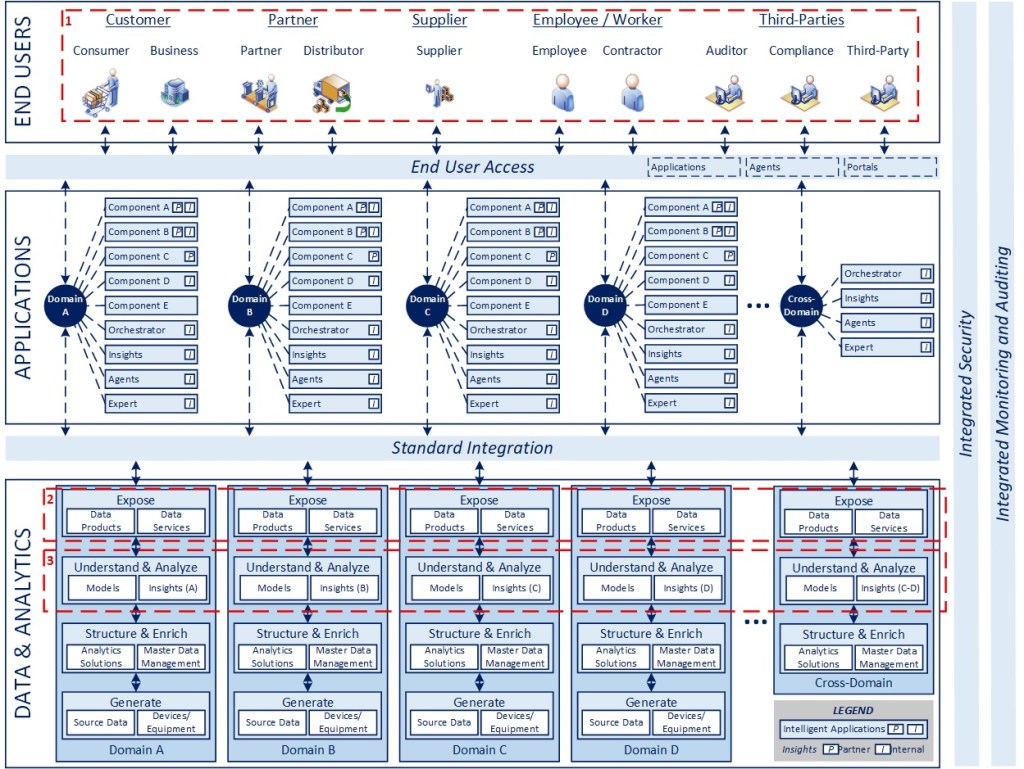

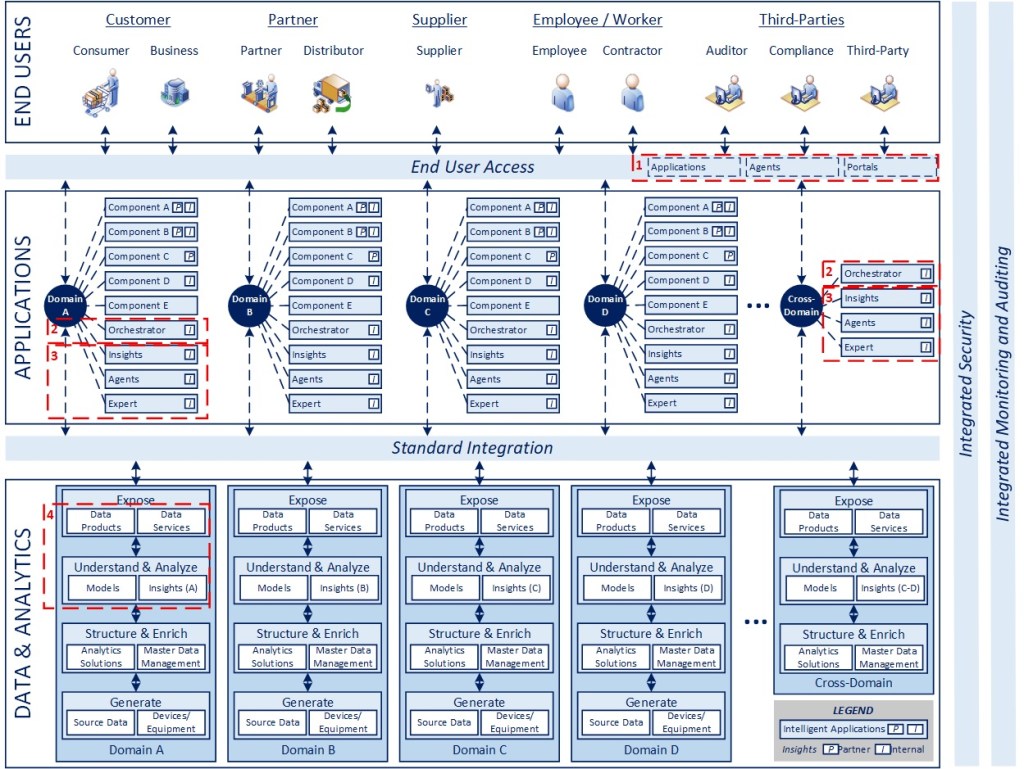

If you’ve made it this far, I wanted to move beyond the theory to a conceptual scenario to help illustrate various situations that could occur in the course of a simplification exercise. The example diagram represents the flow of data across the three initial steps of the process outlined above. The data is logically consistent and traceable across steps in the process if it is helpful in understanding the situation. I limited the number of application types (lower left corner of the diagram) so I could explore multiple scenarios without making the data too overwhelming. In practice, there would be multiple domains and many components in each domain to be considered (e.g., HR is a domain with many components represented as a single application category here), depending on the level of granularity being used for the rationalization effort.

From here, I’ll provide some observations on each major step in the hopes of making some example outcomes clear. I’m not covering the financial analysis given it would make things even more complicated to represent, but for the sake of argument, we can assume that there is financial opportunity associated with reducing the number of applications and instances in place

Notes on the Current State

Some observations on the current state based on the data collected:

- The organization has a limited set of corporate applications for Finance, Procurement, and HR, but most of the core applications are relegated to individual business units (there are three in this example) and manufacturing facilities (there are four)

- Business Operation 1 is the largest commercial entity, sharing the same HR and Procurement solutions, though with unique copies of its own, a different instance of the core accounting system that is managed separately, with two facilities (1 and 2), using different instances of the same MES system, a common WMS system, and a set of unique fringe applications in most other functional categories, some of which overlap or complement those at the business unit level. Despite these differences in footprint, facilities 1 and 2 are highly similar from an operational/business process standpoint

- Business Operations 2 and 3 are smaller commercial entities, running on a different HR system and a different instance of the Procurement solutions than Corporate, a different instance of the core accounting system that is managed separately in one and a unique accounting system in the other, with one facility each (3 and 4), using different MES systems, different instances of the same WMS system, and a set of unique fringe applications in most other functional categories, some of which overlap or complement those at the business unit level. Despite these differences in footprint, facilities 3 and 4 are highly similar from an operational/business process standpoint

- All three business entities operate of unique ERP solutions, two of them leverage the same CRM system, though they are on separate instances, so there is no enterprise-level view of customer and financials need to be consolidated at corporate across all three entities using something like Hyperion or OneStream

- The facilities utilize three different EAM solutions for Asset Health today, with two of them (2 and 3) using the same software

- The fringe applications for accounting, EH&S, HR, and Procurement largely exist because of capability gaps in the solutions already available from the corporate or business unit applications

All things considered, the current environment includes 29 unique applications and 15 application instances.

Sounds complicated, doesn’t it?

Well, while this is entirely a made-up scenario meant to help illustrate various simplification opportunities, the fact is that these things do actually happen, especially as you scale up and out an organization, have acquisitions, or partially roll out technology over time.

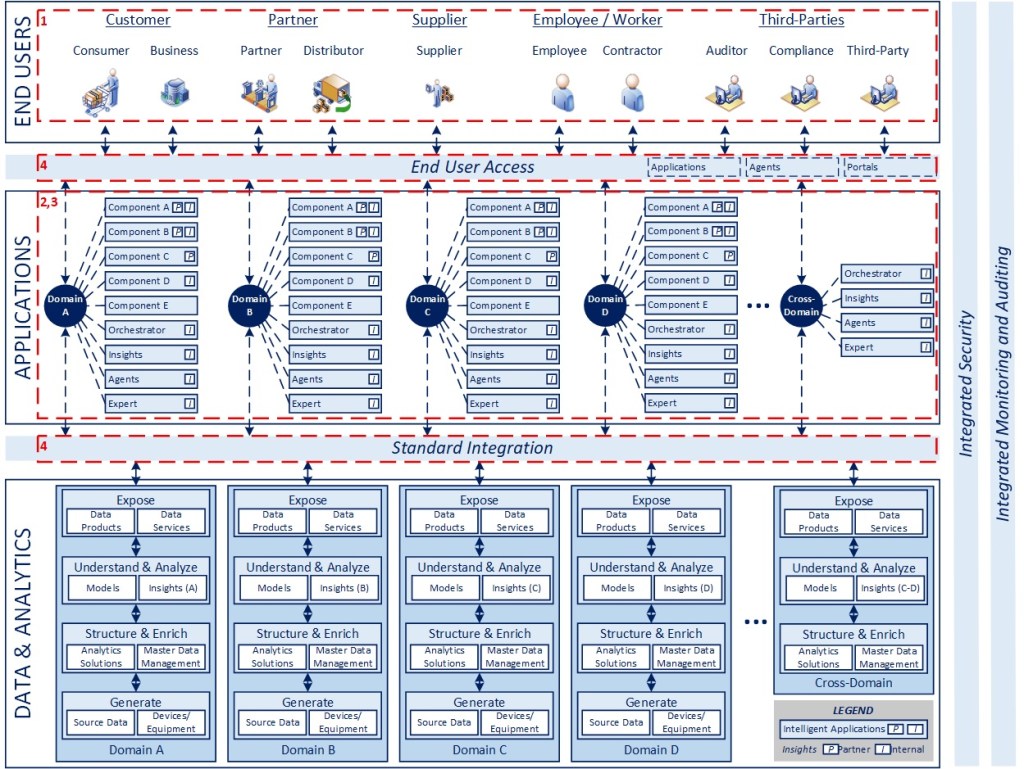

Notes on the Evaluation

Observations based on the analysis performed:

- Having worked with business, portfolio, and application owners to classify and assess the applications in place, a set of systems surfaced as creating higher levels of business value, between mission-critical core (ERP, CRM, Accounting, MES) and supporting/fringe (Procurement, HR, WMS, EH&S, EAM) applications.

- Application A, having been implemented by the largest commercial entity, provides the most capability of any of the solutions in place

- Application D, as the current CRM system in use by two of the units today, likely offers the best potential platform for a future enterprise standard

- Application F likely would make sense as an enterprise standard platform for accounting, though there is something about Application I currently in Facility 3 that provides unique capability at a day-to-day level

- Application V is the best of the MES solutions from a fit and technology standpoint and is in place at two of the facilities today, though running on separate instances

- Application K is already in place to support Procurement across most of the enterprise, though instances are varied and Applications L and M exist at the facility level because of gaps in capability today

- Applications M and O surface as the best technical solutions in the EH&S space, with all of the others providing equal or lesser business value and technical quality

- Application S stands out among other HR solutions as being a very solid technology platform

- Application AB is the best of the EAM solutions both in terms of business capability and technical quality

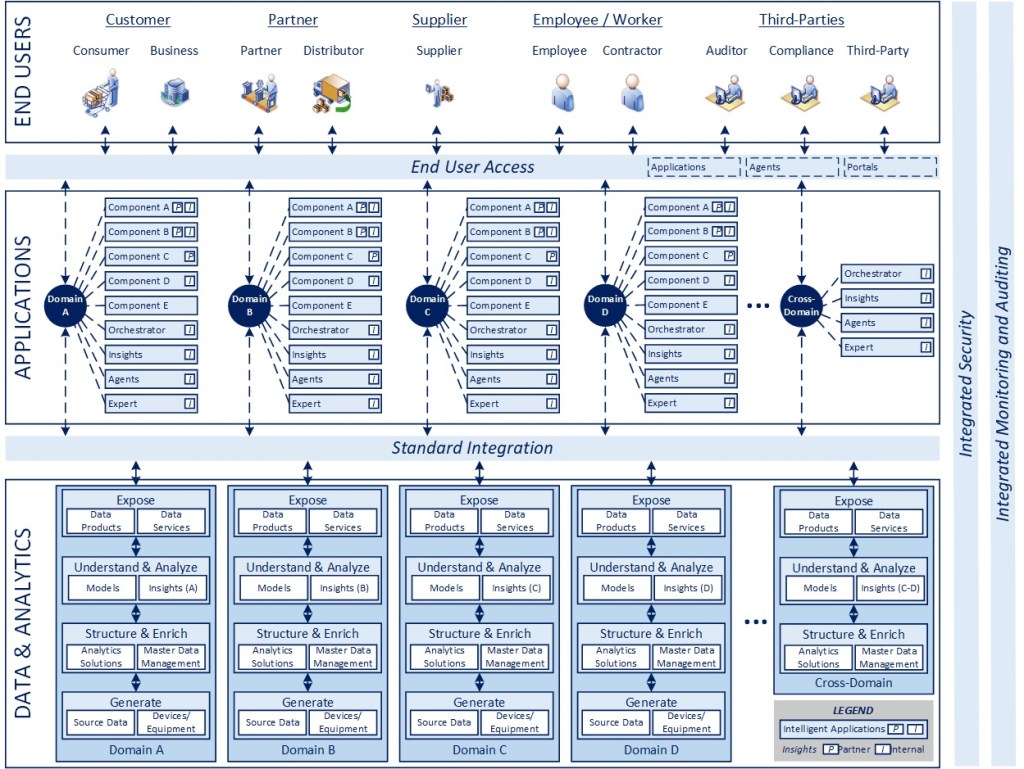

Notes on the Strategy

The overall simplification strategy begins with the desire to standardize operations for smaller business entities 2 and 3 (operating blueprint B) and to run facilities in a more standard way between those supporting the larger commercial unit (facility blueprint A) and those supporting the smaller ones (facility blueprint B).

From a big bets standpoint:

- ERP: Make improvements to Application A supporting business operation 1 so that the company can move from three ERPs to one, using a separate instance for the smaller operating units.

- CRM: Make any necessary enhancements to Application D so that it can be run as a single enterprise application supporting all three business units (removing it from their footprint to manage), providing a mechanism to have a single view of the customer and reduced operating complexity and cost

- Accounting: Given it is already largely in place across businesses, make improvements to Application F so it can serve as a single enterprise finance instance and remove it from footprint of the individual units. In the case of the facility-level requirements, making updates to accounting Application I and standardizing on that application for the small business manufacturing facilities.

- MES: Finally, standardize on Application V across facilities, with a unique instance being used to operate large and small business facilities respectively

For Operational Improvements:

- Procurement and HR: Similar to CRM and Accounting, standardize on Application K and S so that they can be maintained and operated at the enterprise level

- EH&S: Assuming there are differences how they operate, standardize to Applications M and O as solutions for large and smaller units respectively, eliminating all other applications in place

- WMS: Y is already the standard for large facilities, so no action is needed there. For smaller facilities, consolidate to a single instance to support both facilities rather than maintain two versions of Application Z

- EAM: standardize to a single, improved version of Application AB and eliminate other applications currently in place

- Finally, for low value applications like H and M, to review and ensure no dependencies or issues exist, but to sunset those applications and reduce complexity and any associated cost outright

Post-implementation, the future environment would include 12 unique applications and 2 application instances, which is a net reduction of 17 applications (59%) and 13 instances (87%), likely with a substantial cost impact as well.

Wrapping Up

I realized in chalking out this article that it would be a substantial amount of information, but it is aimed at practitioners in the interest of sharing some perspective on considerations involved in doing rationalization work. In my experience, what seems fairly straightforward on paper (including in my example above) generally isn’t for many reasons that are organizational and process-driven in nature. That being said, there is a lot of complexity in many organizations to be addressed and so hopefully some of the ideas covered will be helpful in making the process a little more manageable.

I hope the ideas were worth considering. Thanks for spending the time to read them. Feedback is welcome as always.

-CJG 10/26/2025