I have all this complexity, and I’m not sure what I can do about it…

In medium- to large-scale organizations, complexity is part of daily life. Systems build up over time, as does the integration between them, and eventually it is easy to have a very complex spider web of applications and data solutions across an enterprise, some of which provide significant value, some that are there for reasons no one can explain… but the solution is somehow still viewed to be essential.

Returning to a simplified technology footprint is often desirable for multiple reasons:

- A significant portion of ongoing spend is required to support and maintain what’s in place, hampering efforts to innovate, improve, or create new, more highly valued capabilities

- New delivery efforts take a long time, because there is so much to consider in implementation both to integrate what exists and also not to break something in the process of making changes

- Technologies continue to advance and security exposures come about, and a large portion of IT spend becomes consumed in “modernization” of things that don’t create enough value to justify the spend, but you don’t have a choice not to invest in them given they also can’t be retired

- People enter and leave the organization over time. Onboarding people takes time and cost, leading to suboptimized utilization for an extended period of time, and exits can orphan solutions where the risks for modifying or retiring something are difficult to evaluate

The problem is that simplification, like modernization, is often treated as a point-in-time activity and not an ongoing maintenance effort as part of an annual planning and portfolio management process. As a result, assets accumulate, and the cost for addressing the associated complexity and technical debt increases substantially the longer it takes to address the situation. I will address optimizing overall IT productivity in a separate article, but this is definitely an issue that exists in many organizations today.

Having recently written about the intangibles associated with simplification, the focus of this article is establishing the foundation upon which a rationalization effort can be built, because the way you define scope and the tools you use to manage the process matter.

A quick note on Enterprise Architecture…

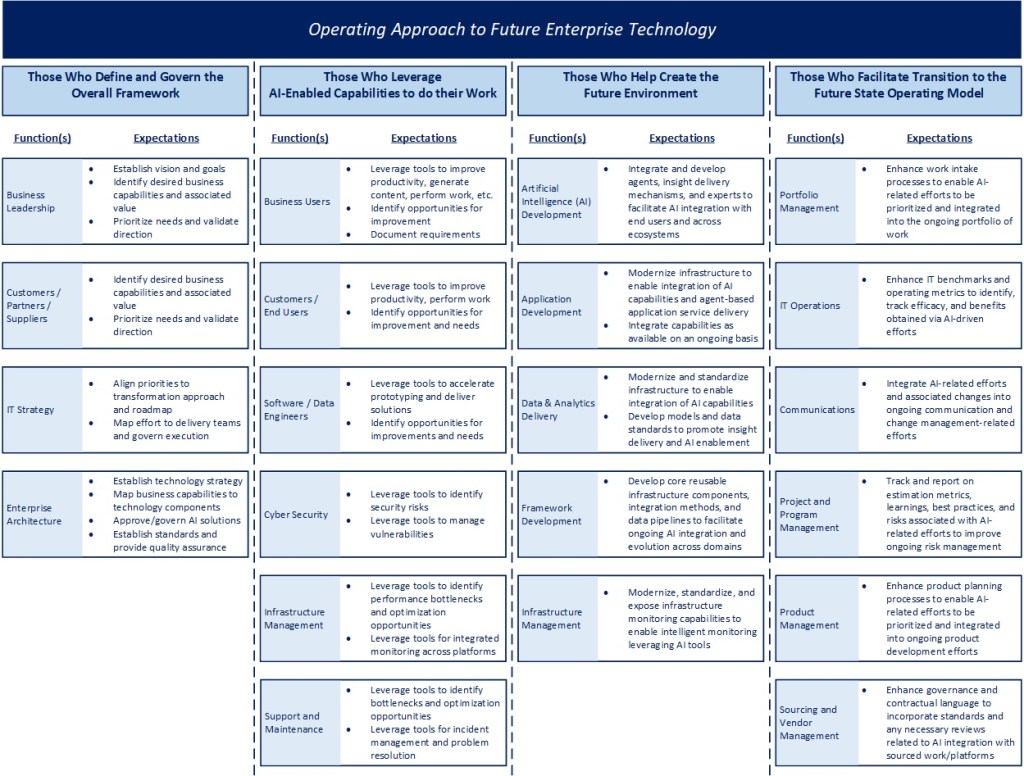

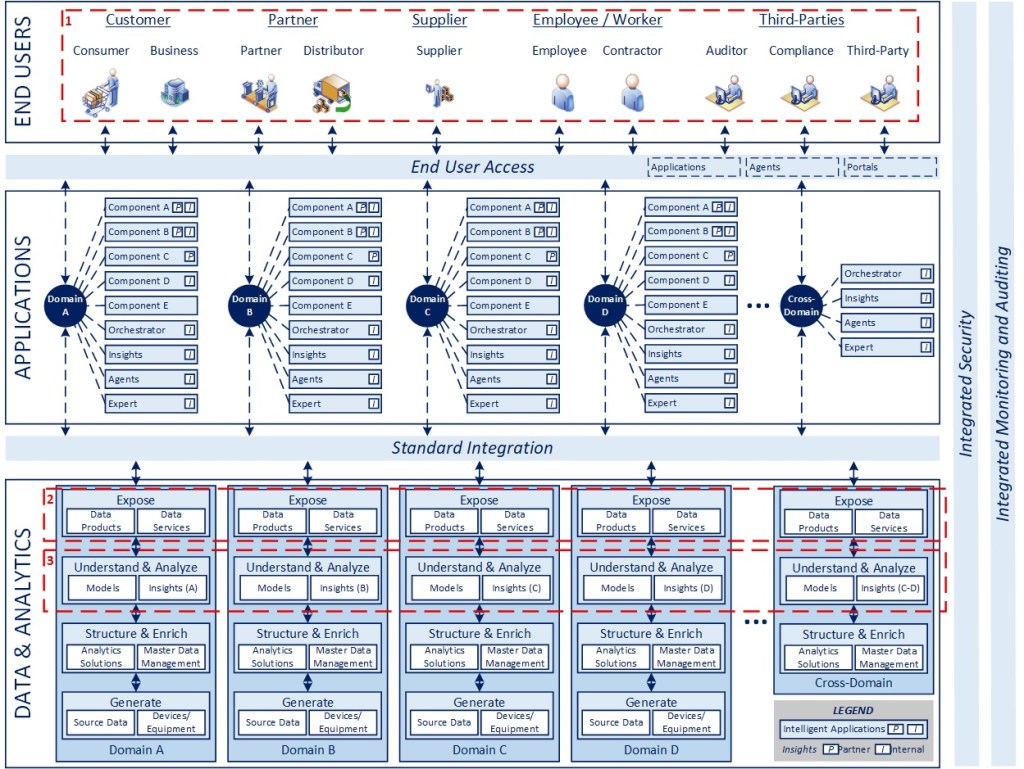

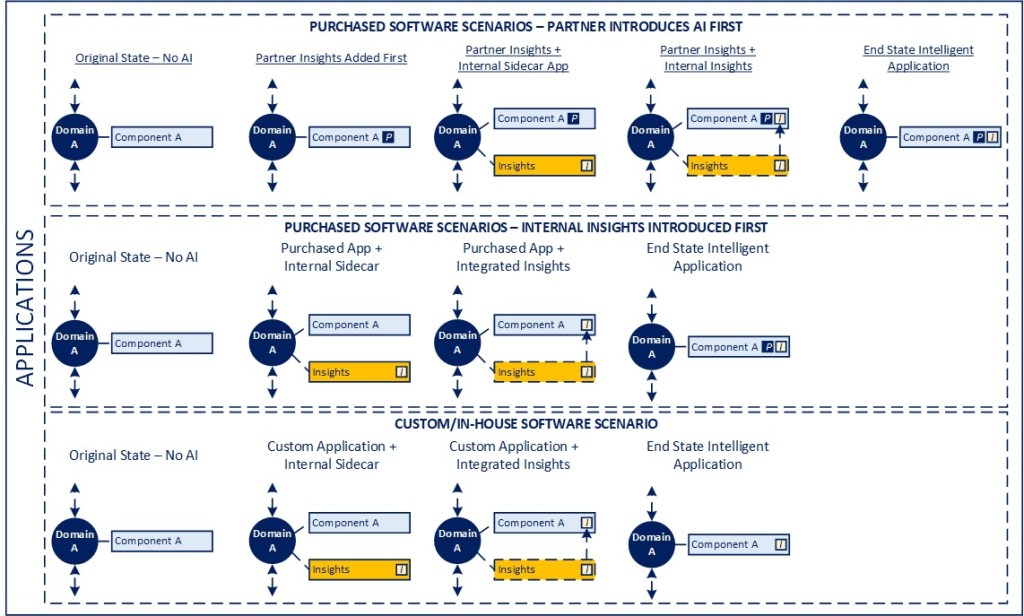

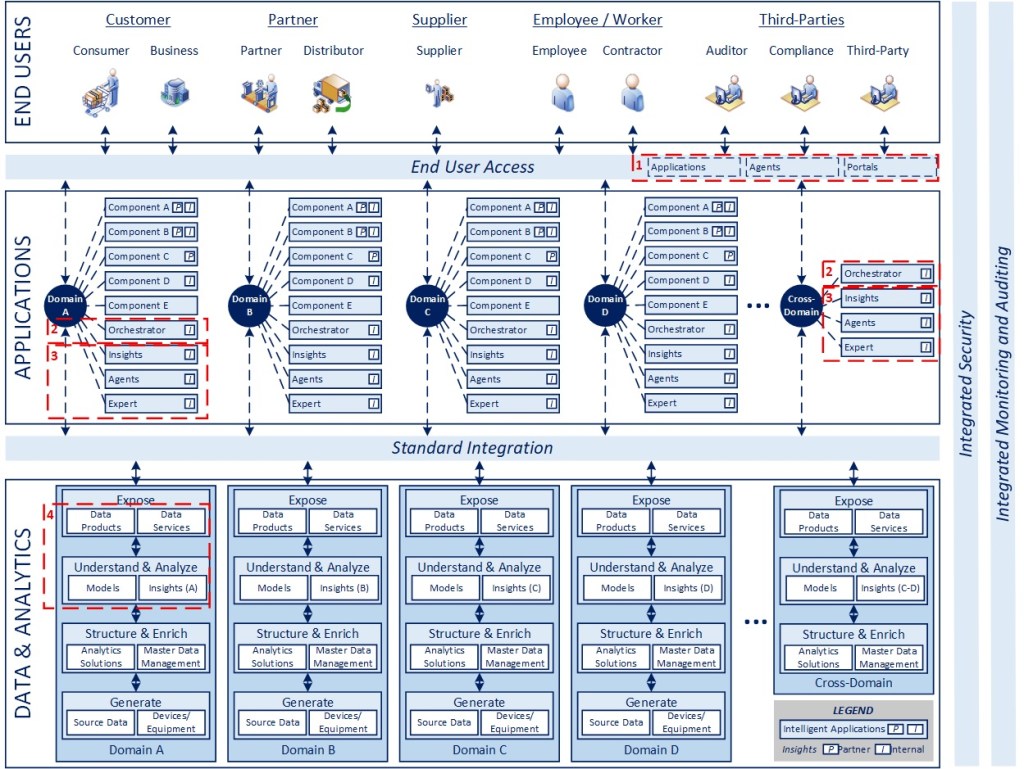

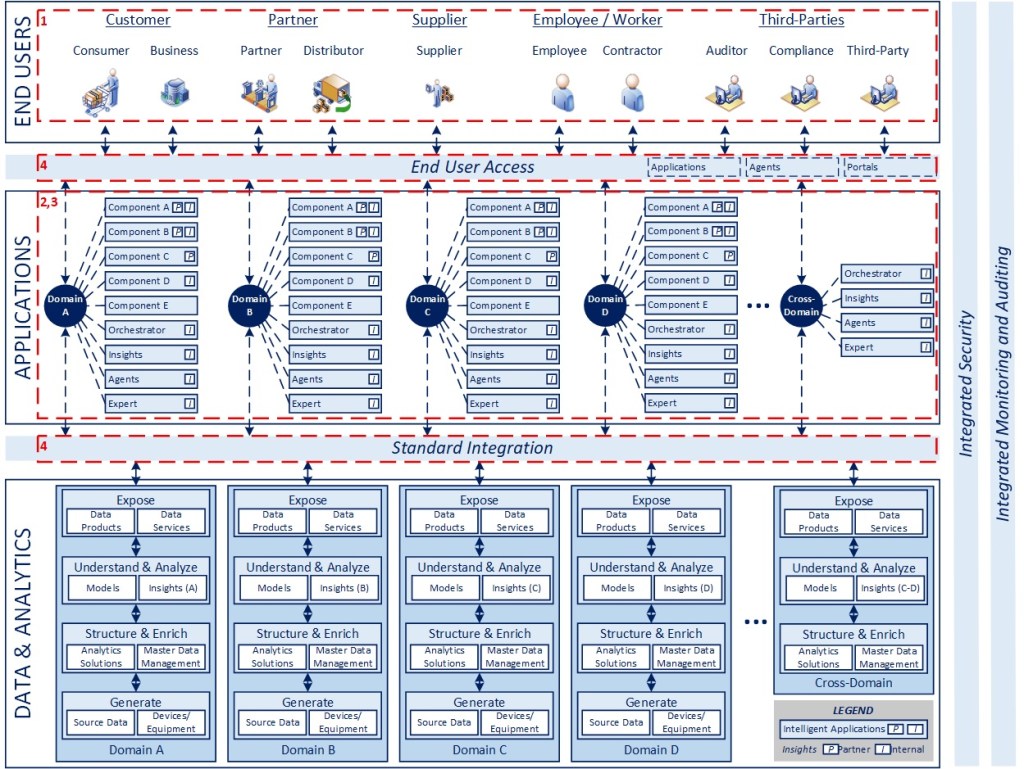

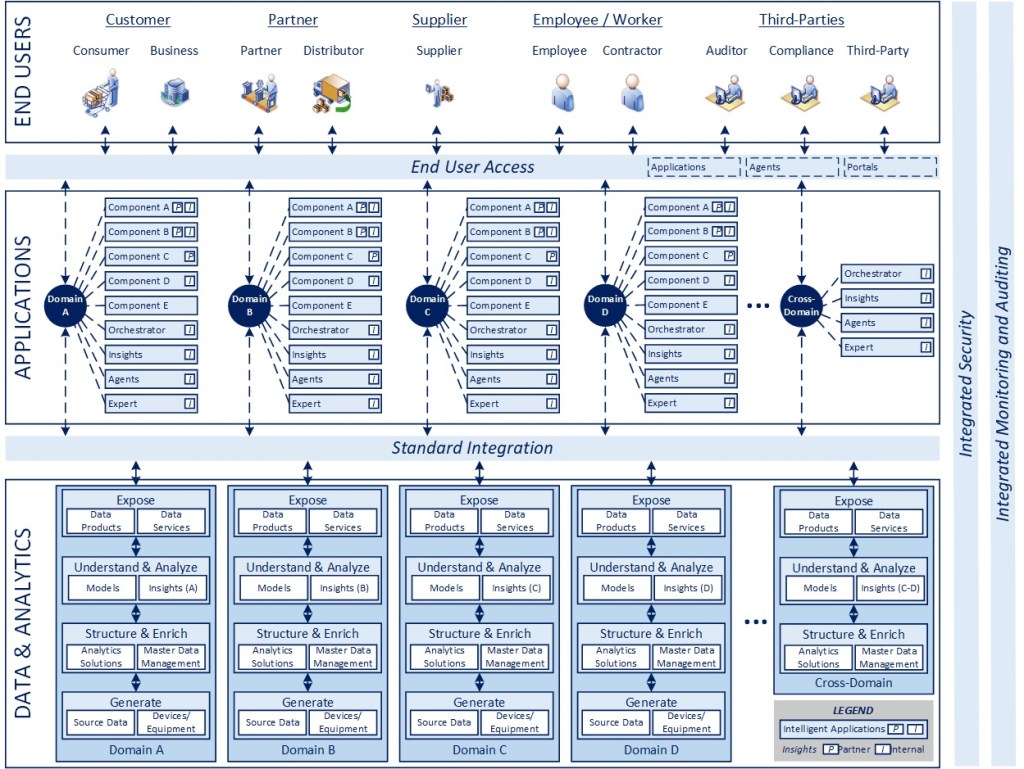

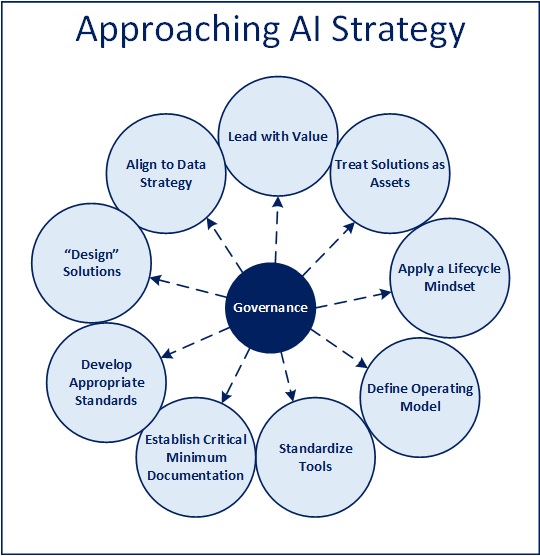

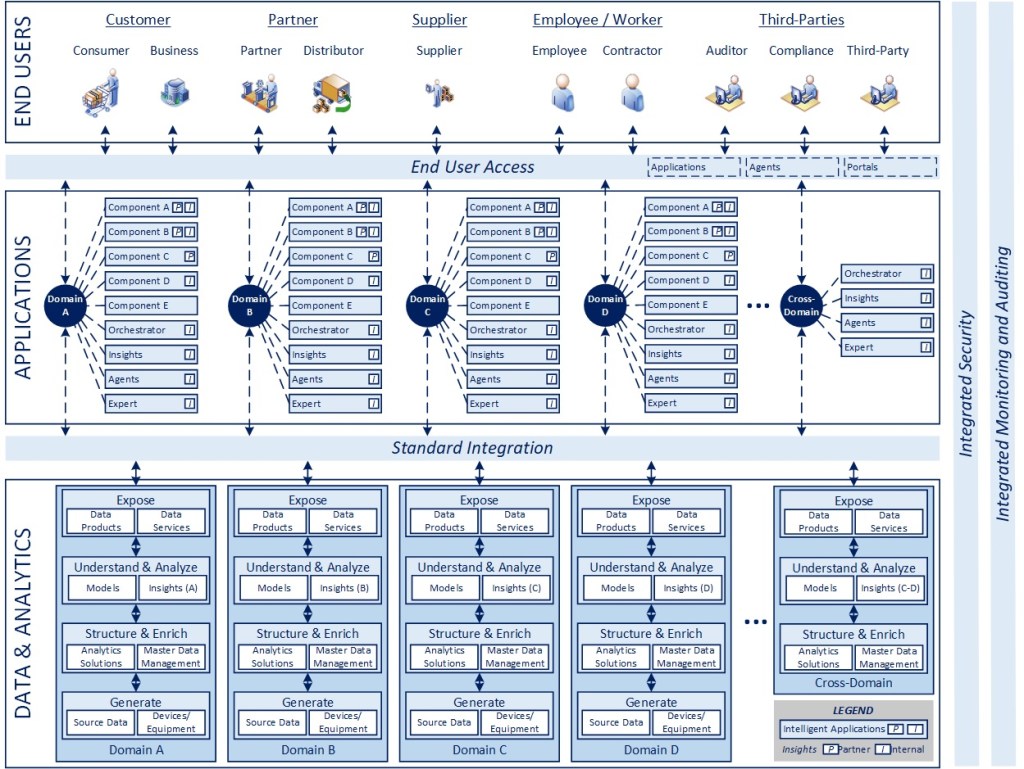

While the focus of this series of articles is specifically on app rationalization, my point of view on enterprise architecture overall is no different than what is outlined in the recent 7-part series on “The Intelligent Enterprise in an AI World” (Intelligent Enterprise Recap). The future of technology will move to a producer/consumer model, involving highly configurable, intelligent applications, with a heavy emphasis on standard integration and orchestration (largely through agentic AI), organized via connected domain-based ecosystems.

While the overall model and framework is the same, the focus in this series is the process for identifying and simplifying the application footprint, where applications are the “components” referenced above.

Establishing the Foundation

Infrastructure

In a perfect world, any medium or large organization should have some form of IT Asset Management (ITAM) solution in place to track and manage assets, identify dependencies, enable ongoing discovery and license management, and a host of other things. In a perfect world, it can also be integrated with your IT Service Management (ITSM) infrastructure provide a fully traceable mechanism to link assets to incidents and strive to improve reliability and operating performance over time.

Is this kind of infrastructure required for a simplification effort? No.

The goal of rationalization is not boiling the ocean or establishing an end-to-end business aligned enterprise infrastructure for managing the application portfolio, the goal is identifying opportunities to simplify and optimize.

In a perfect world, an enterprise architecture strategy should start with business capabilities, map those to technology capabilities, then translate that into the infrastructure (components and services) required to enable those technology capabilities. It would be wonderful and desirable to lay all of that out in the context of a rationalization effort, but those things take time and investment, and to the extent you are planning to replace and retire a potentially significant portion of what you have, it’s better to reduce the clutter and duplication first (assuming your footprint largely supports and aligns to your business needs) and then clean up and streamline your infrastructure as a secondary priority, with only the retained assets in scope.

In the rare situation where technology is fundamentally believed to be misaligned to the core business needs, it could be necessary and appropriate to start with the business strategy and go top-down from there, but I would assume this would be the exception in most case. Said differently: If you can get your rationalization effort done with the simplest tools you have (e.g., Microsoft Excel), go ahead, just make sure the data is accurate. Buy and leverage a more robust platform later, preferably when you know how you are planning to use it and commit to what it will take to maintain the data, because that is ultimately where their value is established and proven over time.

Scope

What is an application?

One of the deceptive things about rationalization work is how this simple this question appears when you haven’t gone through the exercise before. The problem is that we use a host of things in the course of doing work, built with various technologies in multiple ways, and the way we determine scope in the interest of simplification matters.

Specifically, here is a list of things that potentially you should consider in a rationalization effort and my point of view on whether I’d normally consider them to be in scope:

- Business applications (ERPs, CRM, MES, etc.): This is a given and generally the primary focus.

- Tools (Microsoft Word, Alteryx, Tableau): Generally no. Tools produce content. They generally don’t enable business processes, which is what I consider core to an “application”.

- Third-Party Websites and Platforms (WordPress, PluralSight): In scope, to the degree they are supporting an essential business function or been customized to provide required capabilities

- Citizen-Developed Applications: Generally yes, to the degree there is associated cost

- Analytics/BI Solutions: Generally no. While data marts, warehouses, and so on provide business functionality, I consider analytics and applications to be two distinct technology domains that should be analyzed and rationalized separately, while being integrated into a cohesive overall enterprise architecture strategy

- SharePoint sites: No. SharePoint is used to manage content, not provide functionality.

- SharePoint applications: Generally yes, because there is an associated workflow and business process being enabled.

- Robotic Process Automation (RPA): Generally no. RPA tools tend to act as utilities that automate simple tasks, but don’t provide robust capabilities at the level of an application. There could be exceptions to this, but I would be concerned if an RPA tool was providing a critical capability and wasn’t actually architected, designed, and built as an application to begin with. That is a mismatch from an EA standpoint and likely I’d want to investigate migrating to a more robust and well-architected solution

- Agentic AI Solutions: Yes. While this may be limited today, it will become more prevalent in the coming months and the relationship to existing solutions needs to be understood.

- AI Solutions/Packages: Yes. In this case, by comparison with agentic solutions overlapping applications in a footprint, I’d be interested in looking for duplication and redundancy that may occur because AI adoption is relatively new, governance models are largely immature (if they exist at all) and the probability of having multiple tools that perform essentially the same function in medium- to large-organization is or will be relatively high, very soon.

- Vibe-Coded Solutions: Absolutely yes. These need to be tracked particularly from a security exposure standpoint given how new these technologies are and the associated risk for putting them into production at this stage of the technology’s evolution.

- Mobile Applications: If it is a standalone application, yes, likely should be included. If it is a different form of presentment on a web-enabled application, it theoretically should be included as part of the source application, so no. Depending on the criticality of mobility in the enterprise technology strategy, whether an app is mobile enabled could be part of the inventory data gathered, but only if it is critical to the strategy, otherwise I would leave it out

- IoT Devices: No. Physical assets and devices should be managed and rationalized separately as part of a device strategy (again, that integrates with an overall enterprise architecture)

So, the list above contains more than “business applications”, which is why I said scope can be tricky in a simplification / rationalization effort.

Beyond the considerations mentioned above, a key question to consider on whether any of these additional types of assets is in scope is: is there associated cost to maintain and support the asset, is there cyber security exposure, or are there compliance or privacy-related considerations with it. Ultimately, any or all of these dimensions need to be considered in the exercise, because simplification not only should reduce complexity and cost, it should reduce security exposure and business risk.

Wrapping Up

From here, the focus will pivot to the process itself and a practical example to help illustrate the concepts put into more of a “real world” scenario.

I hope the ideas were worth considering. Thanks for spending the time to read them. Feedback is welcome as always.

-CJG 10/24/2025