Does having more data automatically make us more productive or effective?

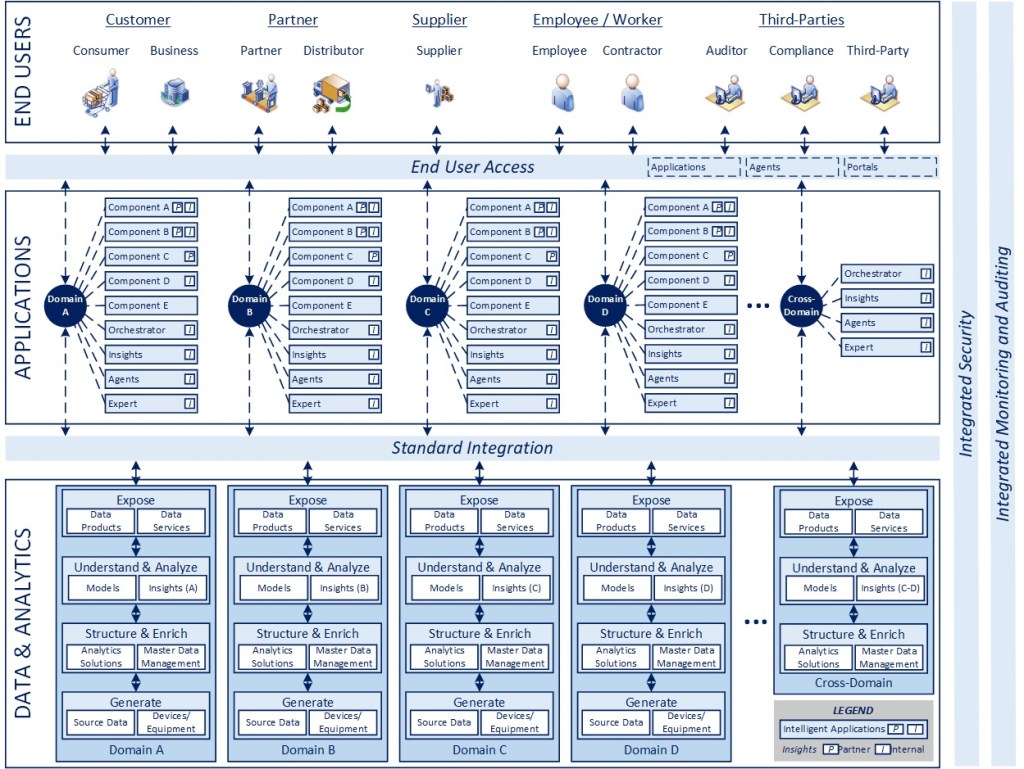

When I wrote the original article on “The Intelligent Enterprise”, I noted that the overall ecosystem for analytics needed to change. In many environments, data is moved from applications to secondary solutions, such as data lakes, marts, or warehouses, enriched and integrated with other data sets, to produce analytical outputs or dashboards to provide transparency into operating performance. Much of this is reactive and ‘after-the-fact’ analysis of things we want to do right or optimize the first time, as events occur. The extension of that thought process was to move those insights to the front of the process, integrate them with the work as it is performed, and create a set of “intelligent applications” that would drive efficiency and effectiveness to different levels than we’ve been able to accomplish before. Does this eliminate the need for downstream analytics, dashboards, and reporting? No, for many reasons, but the point is to think about how we can make the future data and analytics environment about establishing a model that enables insight-driven, orchestrated action.

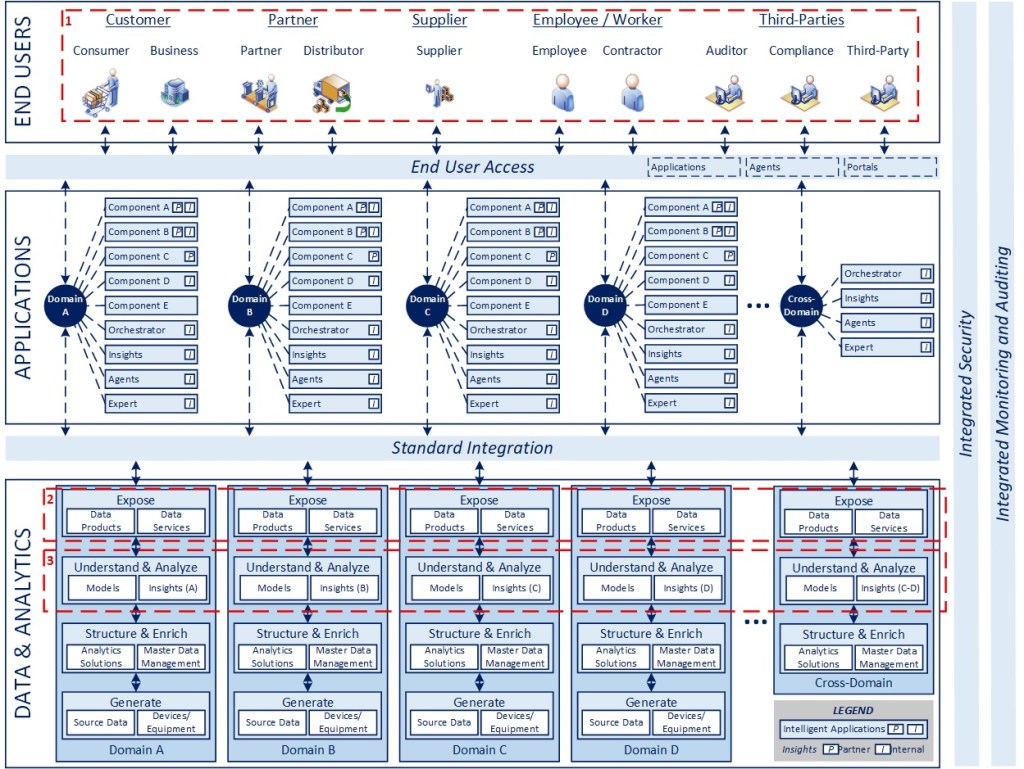

This is the fifth post in a series focused on where I believe technology is heading, with an eye towards a more harmonious integration and synthesis of applications, AI, and data… what I previously referred to in March of 2022 as “The Intelligent Enterprise”. The sooner we begin to operate off a unified view of how to align, integrate, and leverage these oftentimes disjointed capabilities today, the faster an organization will leapfrog others in their ability to drive sustainable productivity, profitability, and competitive advantage.

Design Dimensions

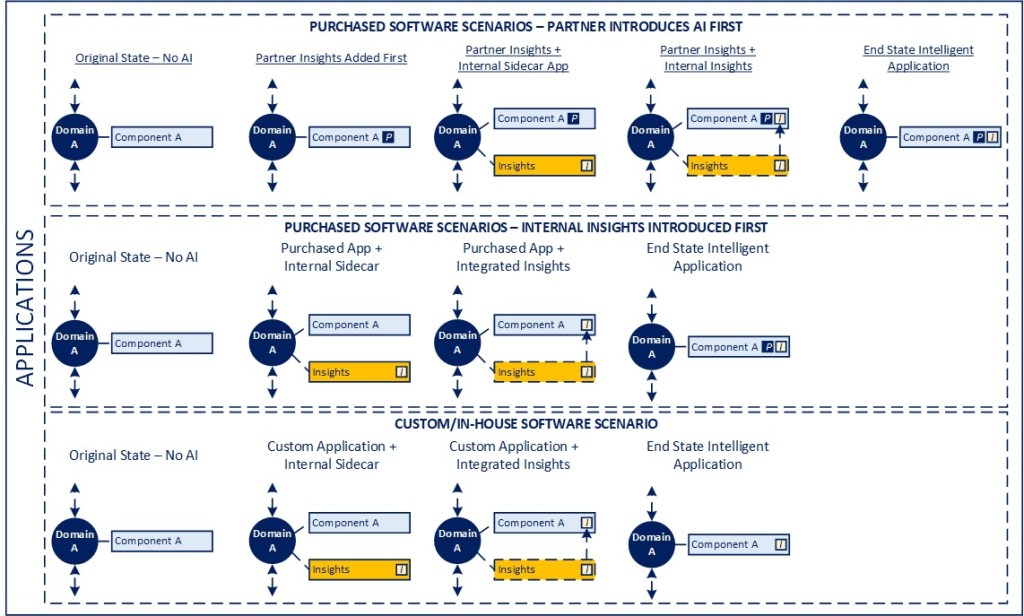

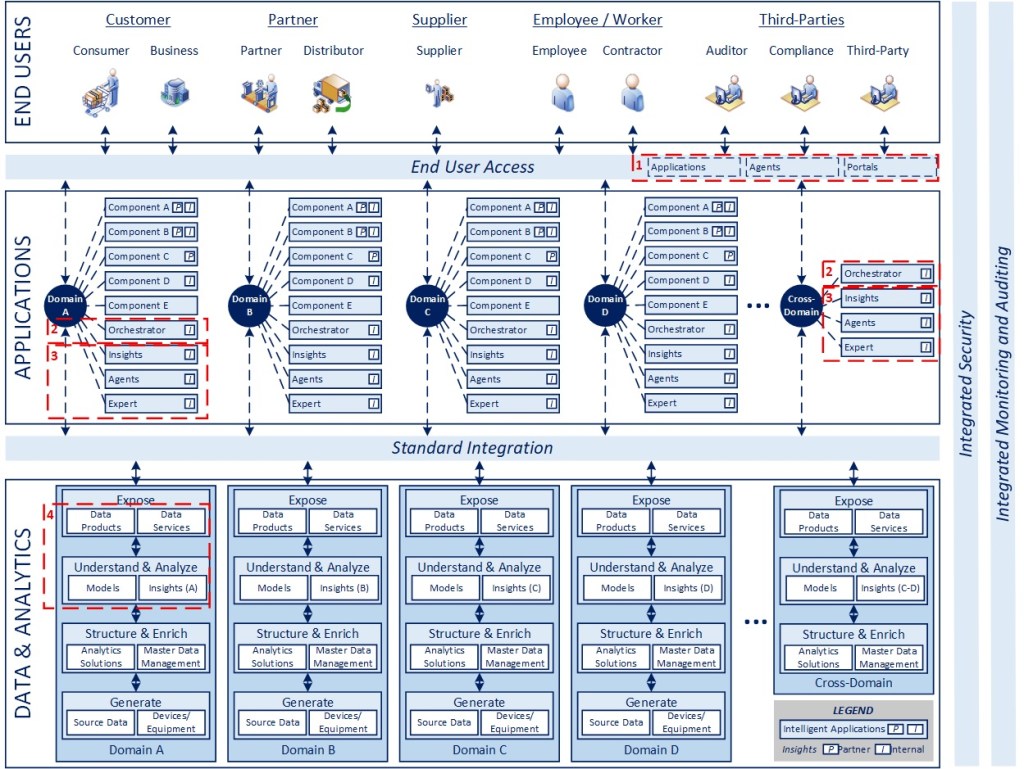

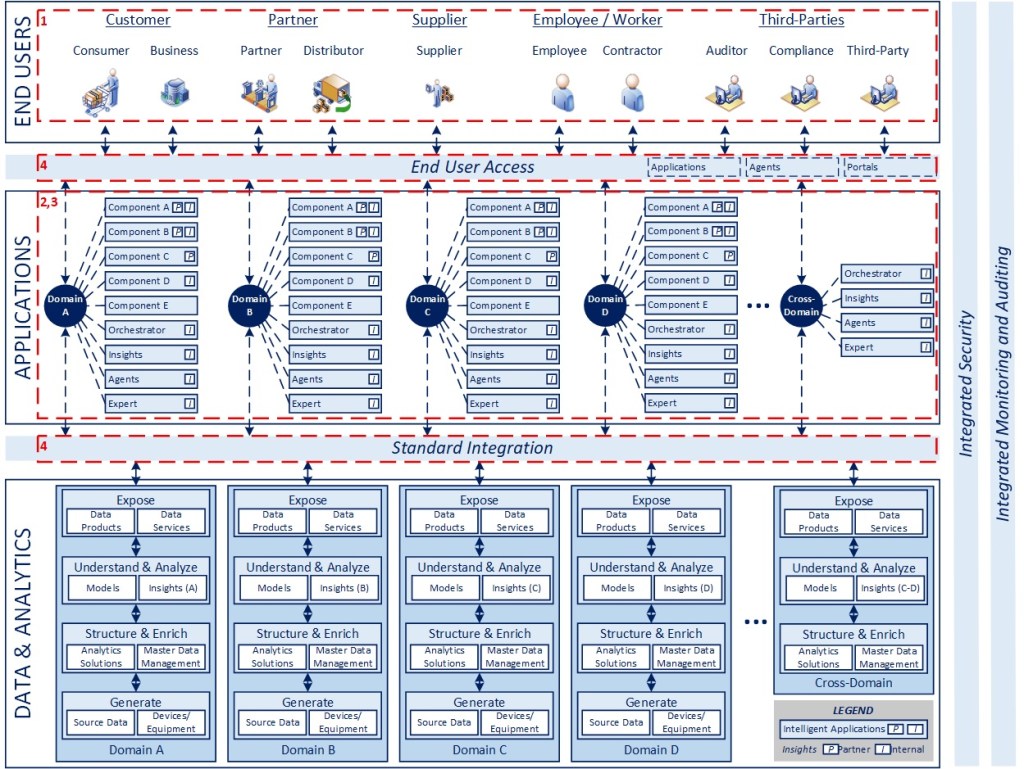

In line with the blueprint above, articles 2-5 highlight key dimensions of the model in the interest of clarifying various aspects of the conceptual design. I am not planning to delve into specific packages or technologies that can be used to implement these concepts as the best way to do something always evolves in technology, while design patterns tend to last. The highlighted areas and associated numbers on the diagram correspond to the dimensions described below.

Starting with the Consumer (1)

“Just give me all the data” is a request that isn’t unusual in technology. Whether that is a byproduct of the challenges associated with completing analytics projects, a lack of clear requirements, or something else, these situations cause an immediate issue in practice: what is the quality of the underlying data and what are we actually trying to do with it?

It’s tempting to start an analytics effort from the data storage and to work our way up the stack to the eventual consumer. Arguably, this is a central premise in being “data-centric.” While I agree with the importance of data governance and management (the next topic), it doesn’t mean everything is relevant or useful to an end consumer, and too much data very likely just creates management overhead, technical complexity, and information overload.

A thoughtful approach needs to start with identifying the end consumers of the data, their relative priority, information and insights needs, and then developing a strategy to deliver those capabilities over time. In a perfect world, that should leverage a common approach and delivery infrastructure so that it can be provided in iterations and elaborated to include broader data sets and capabilities across domains over time. The data set should be on par with having an integrated data model and consistent way of delivering data products and analytics services that can be consumed by intelligent applications, agents, and solutions supporting the end consumer.

As an interesting parallel, it is worth noting that ChatGPT is looking to converge their reasoning and large language models from 4x into a single approach for their 5x release so that end customers don’t need to be concerned with having selected the “right” model for their inquiry. It shouldn’t matter to the data consumer. The engine should be smart enough to leverage the right capabilities based on the nature of the request, and that is what I am suggesting in this regard.

Data Management and Governance (2)

Without the right level of business ownership, the infrastructure for data and analytics doesn’t really matter, because the value to be obtained from optimizing the technology stack will be limited by the quality of the data itself.

Starting with master data, it is critical to identify and establish data governance and management for the critical, minimum amount of data in each domain (e.g., customer in sales, chart of accounts in finance), and the relationship between those entities in terms of an enterprise data model.

Governing data quality has a cost and requires time, depending on the level of tooling and infrastructure in place, and it is important to weigh the value of the expected outcomes in relation to the complexity of the operating environment overall (people, process, and technology combined).

From Content to Causation (3)

Finally, with the level of attention given to Generative AI and LLMs, it is important to note the value to be realized when we shift our focus from content to processes and transactions in the interest of understanding causation and influencing business outcomes.

In a manufacturing context, the increasing level of interplay between digital equipment, digital sensors, robotics, applications, and digital workers, there is a significant opportunity to orchestrate, gather and analyze increasing volumes of data, and ultimately optimize production capacity, avoid unplanned events, and increase the safety and efficacy of workers on the shop floor. This requires deliberate and intentional design, with outcomes in mind.

The good news is that technologies are advancing in their ability to analyze large data sets and derive models to represent the characteristics and relationships across various actors in play and I believe we’ve only begun to scratch the surface on the potential for value creation in this regard.

Summing Up

Pulling back to the overall level, data is critical, but it’s not the endgame. Designing the future enterprise technology environment is about exposing and delivering the services that enable insightful, orchestrated action on behalf of the consumers of that technology. That environment will be a combination of applications, AI, and data and analytics, synthesized into one meaningful, seamless experience. The question is how long it will take us to make that possible. The sooner we begin the journey of designing that future state with agility, flexibility, and integration in mind, the better.

Having now elaborated the framework and each of the individual dimensions, the remaining two articles will focus on how to approach moving from the current to future state and how to think about the organizational implications on IT.

Up Next: Managing Transition

I hope the ideas were worth considering. Thanks for spending the time to read them. Feedback is welcome as always.

-CJG 08/03/2025