Overview

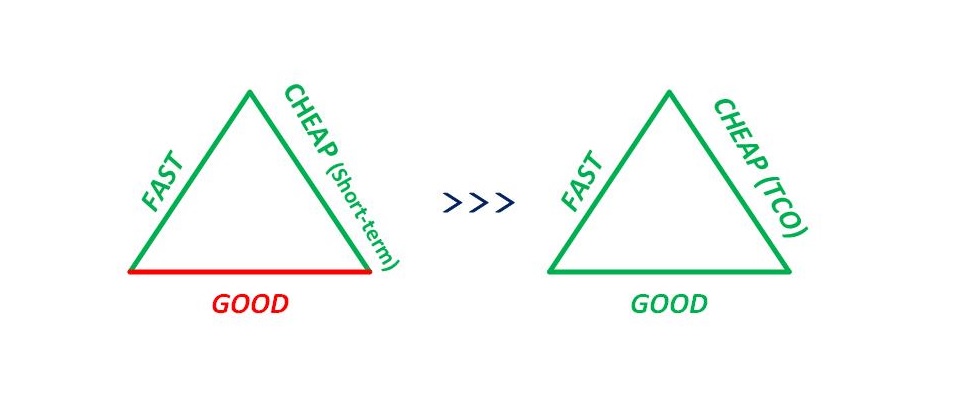

In my first blog article back in 2021, I wrote that “we learn to value experience only once we actually have it”… and one thing I’ve certainly realized is that it’s much easier to do something quickly than to do it well. The problem is that excellence requires discipline, especially when you want to scale or have sustainable results, and that often comes into conflict with a natural desire to achieve speed in delivery.

There is a tremendous amount of optimism in the transformative value AI can create across a wide range of areas. While much continues to be written about various tools, technologies, and solutions, there is value in having a structured approach to developing AI strategy and how we will govern it once it is implemented across an organization.

Why? We want results.

Some historical examples on why there is a case for action:

- Many organizations have leveraged SharePoint as a way to manage documents. Because it’s relatively easy to use, access to the technology generally is provided to a broad set of users, with little or no guidance on how to use it (e.g., metatagging strategy), and over time there becomes a sprawl of content that may contain critical, confidential, or proprietary information with limited overall awareness of what exists and where

- In the last number of years, Citizen Development has become popular, with the rise of low code, no code, and RPA tools, creating accessibility to automation that is meant to enable business (and largely non-technical) resources to rapidly create solutions, from the trivial to relatively complex. Quite often these solutions aren’t considered part of a larger application portfolio, are managed with little or no oversight, and become difficult to integrate, leverage, or support effectively

- In data and analytics, tools like Alteryx can be deployed across a broad set of users who, after they are given access to requested data sources, create their own transformations, dashboards, and other analytical outputs to inform ongoing business decisions. The challenge occurs when the underlying data changes, is not understood properly (and downstream inferences can be incorrect), or these individuals leave or transition out of their roles and the solutions they built are not well understood or difficult for someone else to leverage or support

What these situations have in common is the introduction of something meant to serve as an enabler that has relative ease of use and accessibility across a broad audience, but where there also may be a lack of standards and governance to make sure the capabilities are introduced in a thoughtful and consistent manner, leading to inefficiency, increased cost, and lost opportunity. With the amount of hype surrounding AI, the proliferation of tools, and general ease of use that they provide, the potential for organizations to create a mess in the wake of their experimentation with these technologies seems very significant.

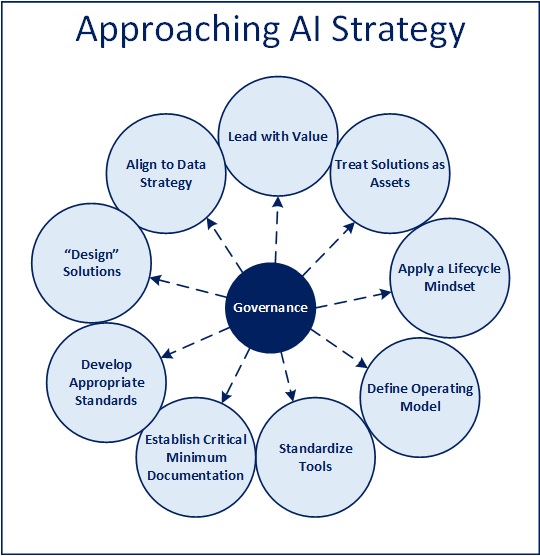

The focus of the remainder of this article is to explore some dimensions to consider in developing a strategy for the effective use and governance of AI in an organization. The focus will be on the approach, not the content of an AI strategy, which can be the subject of a later article. I am not suggesting that everything needs to be prescriptive, cumbersome, or bureaucratic to the point that nothing can get done, but I believe it is important to have a thoughtful approach to avoid the pitfalls that are common to these situations.

To the extent that, in some organizations, “governance” implies control versus enablement or there are historical real or perceived IT delivery issues, there may be concern with heading down this path. Regardless of how the concepts are implemented, I believe they are worth considering sooner rather than later, given we are still relatively early in the adoption process of these capabilities.

Dimensions to Consider

Below are various aspects of establishing a strategy and governance process for AI that are worth consideration. I listed them somewhat in a sequential manner, as I’d think about them personally, though that doesn’t imply you can’t explore and elaborate as many as are appropriate in parallel, and in whatever order makes sense. The outcome of the exercise doesn’t need to be rigid mandates, requirements, or guidelines per se, but nearly all of these topics likely will come up implicitly or otherwise as we delve further into leveraging these technologies moving forward.

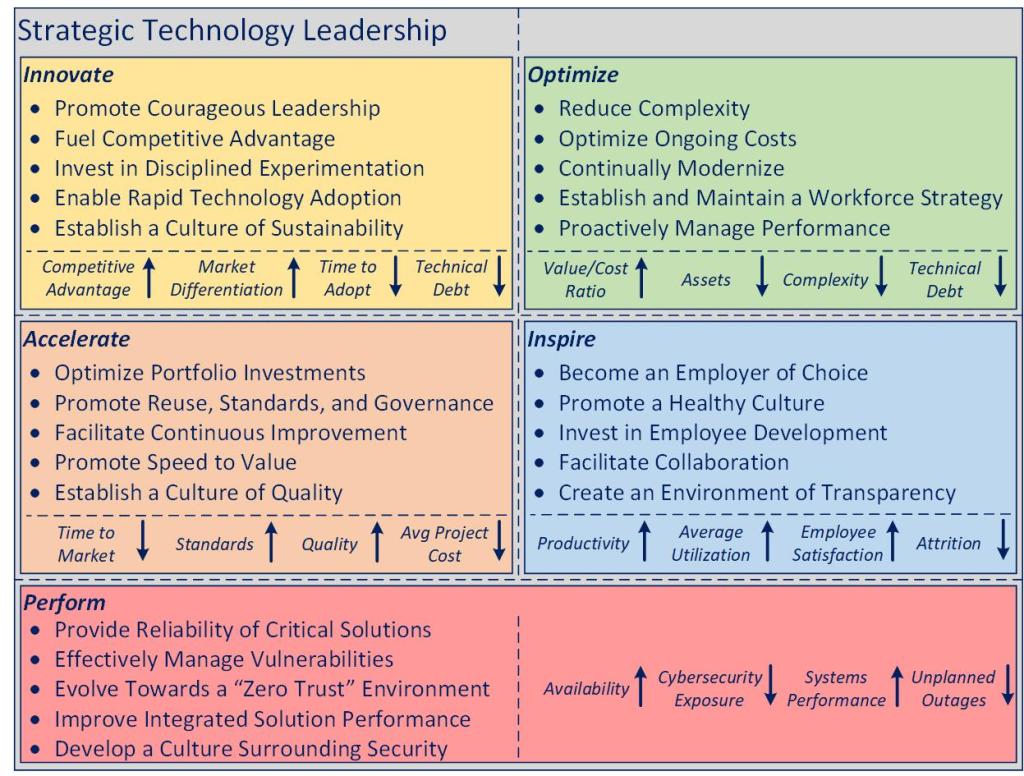

Lead with Value

The first dimension is probably the most important in forming an AI strategy, which is to articulate the business problems being solved and value that is meant to be created. It is very easy with new technologies to focus on the tools and not the outcomes and start implementing without a clear understanding of the impact that is intended. As a result, measuring the value created and governing the efficacy of the solutions delivered becomes extremely difficult.

As a person who does not believe in deploying technology for technology’s sake, identifying, tracking, and measuring impact is important in knowing we will ultimately make informed decisions in how we leverage new capabilities and invest in them appropriately over time.

Treat Solutions as Assets

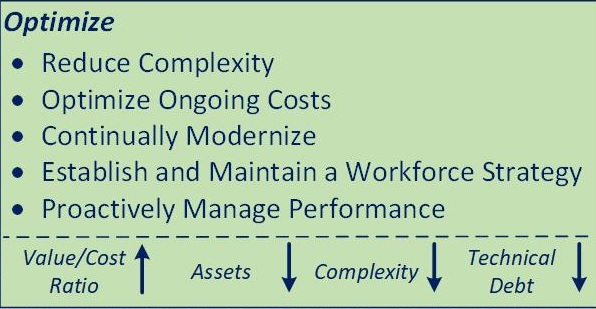

Along the lines of the above point, there is risk associated with being consumed by what is “cool” versus what is “useful” (something I’ve written about previously), and treating new technologies like “gadgets” versus actual business solutions. Where we treat our investments as assets, the associated discipline we apply in making decisions surrounding them should be greater. This is particularly important in emerging technology because the desire to experiment and leverage new tools could quickly become unsustainable as the number of one-off solutions grows and is unsupportable, eventually draining resources from new innovation.

Apply a Lifecycle Mindset

When leveraging a new technical capability, I would argue that we should look for opportunities to think of the full product lifecycle when it comes to how we identify, define, design, develop, manage, and retire solutions. In my experience, the identify (finding new tools) and develop (delivering new solutions) aspects of the process receive significant emphasis in a speed-to-market environment, but the others much less so, and often to the overall detriment of an organization when they quickly are saddled with the resulting technical debt that comes from neglecting some of the other steps in the process. This doesn’t necessarily imply a lot of additional steps, process overhead, or time/effort to be expended, but there is value created in each step of a product lifecycle (particularly in the early stages) and all of them need to be given due consideration if you want to establish a sustainable, performant environment. The physical manifestation of some these steps could be as simple as a checklist to make sure there aren’t blind spots that arise later on that were avoidable or that create business risk.

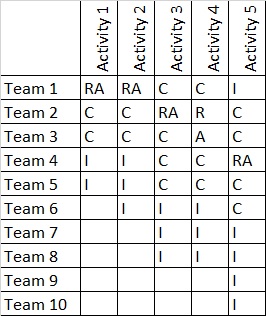

Define Operating Model

Introducing new capabilities, especially ones where the barrier to entry/ease of use allows for a wide audience of users can cause unintended consequences if not managed effectively. While it’s tempting to draw a business/technology dividing line, my experience has been that there can be very technically capable business consumers of technology and very undisciplined technologists who implement it as well. The point of thinking through the operating model is to identify roles and responsibilities in how you will leverage new capabilities so that expectations and accountability is clear, along with guidelines for how various teams are meant to collaborate over the lifecycle mentioned above.

Whether the goal is to “empower end users” by fully distributing capabilities across teams, with some level of centralized support and governance, or fully centralizing with decentralized demand generation (or any flavor in between), the point is to understand who is best positioned to contribute at different steps of the process and promote consistency to an appropriate level so performance and efficacy of both the process and eventual solutions is something you can track, evaluate, and improve over time. As an example, it would likely be very expensive and ineffective to hire a set of “prompt engineers” that operate in a fully distributed manner in a larger organization by comparison with having a smaller, centralized set of highly skilled resources who can provide guidance and standards to a broader set of users in a de-centralized environment.

Following onto the above, it is also worthwhile to decide whether and how these kinds of efforts should show up in a larger portfolio management process (to the extent one is in place). Where AI and agentic solutions are meant to displace existing ways of working or produce meaningful business outcomes, the time spent delivering and supporting these solutions should likely be tracked so there is an ability to evaluate and manage these investments over time.

Standardize Tools

This will likely be one of the larger issues that organizations face, particularly given where we are with AI in a broader market context today. Tools and technologies are advancing at such a rapid rate that having a disciplined process for evaluating, selecting, and integrating a specific set of “approved” tools is and will be challenging for some time.

While asking questions of a generic large language model like ChatGPT, Grok, DeepSeek, etc. and changing from one to the other seems relatively straightforward, there is a lot more complexity involved when we want to leverage company-specific data and approaches like RAG to produce more targeted and valuable outcomes.

When it comes to agentic solutions, there is also a proliferation of technologies at the moment. In these cases, managing the cost, complexity, performance, security, and associated data privacy issues will also become complex if there aren’t “preferred” technologies in place and “known good” ways in which they can be leveraged.

Said differently, if we believe effective use of AI is critical to maintaining competitive advantage, we should know that the tools we are leveraging are vetted, producing quality results, and that we’re using them effectively.

Establish Critical Minimum Documentation

I realize it’s risky to use profanity in a professional article, but documentation has to be mentioned if we assume AI is a critical enabler for businesses moving forward. Its importance can probably be summarized if you fast forward one year from today, hold a leadership meeting, and ask “what are all the ways we are using artificial intelligence, and is it producing the value we expected a year ago?” If the response contains no specifics and supporting evidence, there should be cause for concern, because there will be significant investment made in this area over the next 1-2 years, and tracking those investments is important to realizing the benefits that are being promised everywhere you look.

Does “documentation” mean developing a binder for every prompt that is created, every agent that’s launched, or every solution that’s developed? No, absolutely not, and that would likely be a large waste of money for marginal value. There should be, however, a critical minimum amount of documentation that is developed in concert with these solutions to clarify their purpose, intended outcome/use, value to be created, and any implementation particulars that may be relevant to the nature of the solution (e.g. foundational model, data sets leveraged, data currency assumptions, etc.). An inventory of the assets developed should exist, minimally so that it can be reviewed and audited for things like security, compliance, IP, and privacy-related concerns where applicable.

Develop Appropriate Standards

There are various types of solutions that could be part of an overall AI strategy and the opportunity to develop standards that promote quality, reuse, scale, security, and so forth is significant. Whether it takes the form of a “how to” guide for writing prompts, to data sourcing and refresh standards with RAG-enabled solutions, reference architecture and design patterns across various solution types, or limits to the number of agents that can be developed without review for optimization opportunities… In this regard, something pragmatic, that isn’t overly prescriptive but that also doesn’t reflect a total lack of standards would be appropriate in most organizations.

In a decentralized operating environment, the chance that solutions will be developed in a one-off fashion, with varying levels of quality, consistency, and standardization is highly probable and that could create issues with security, scalability, technical debt, and so on. Defining the handshake between consumers of these new capabilities and those developing standards, along with when it is appropriate to define them, could be important things to consider.

Design Solutions

Again, as I mentioned in relation to the product lifecycle mindset, there can be a strong preference to deliver solutions without giving much thought to design. While this is often attributed to “speed to market” and a “bias towards action”, it doesn’t take long for tactical thinking to lead to a considerable amount of technical debt, an inability to reuse or scale solutions, or significant operating costs that start to slow down delivery and erode value. These are avoidable consequences when thought is given to architecture and design up front and the effort nearly always pays off over time.

Align to Data Strategy

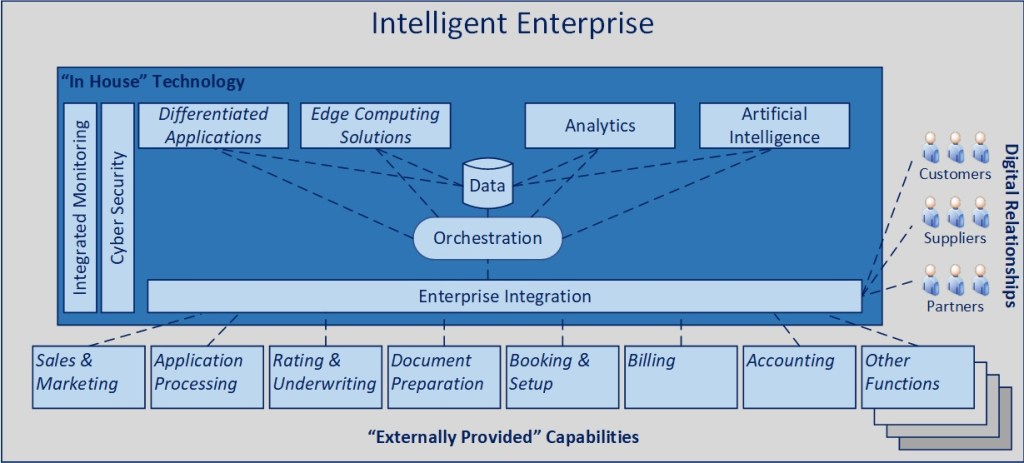

This topic could be an article in itself, but suffice is to say that having an effective AI strategy is heavily dependent on an organization’s overall data strategy and the health of that portfolio. Said differently: if your underlying data isn’t in order, you won’t be able to derive much in terms of meaningful insights from it. Concerns related to privacy and security, data sourcing, stewardship, data quality, lineage and governance, use of multiple large language models (LLMs), effective use of RAG, the relationship of data products to AI insights and agents, and effective ways of architecting for agility, interoperability, composability, evolution, and flexibility are all relevant topics to be explored and understood.

Define and Establish a Governance Process

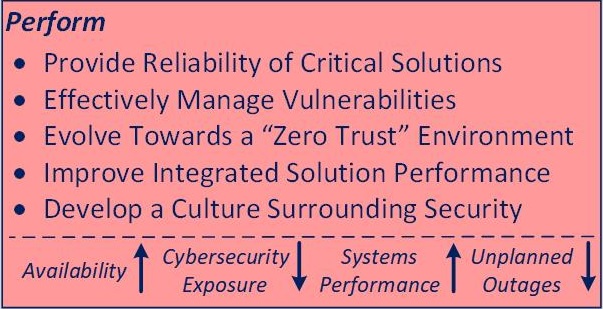

Having laid out the above dimensions in terms of establishing and operationalizing an AI strategy, there needs to be a way to govern it. The goal of governance is to achieve meaningful business outcomes by promoting effective use and adoption of the new capabilities, while managing exposure related to introducing change into the environment. This could be part of an existing governance process or set up in parallel and coordinated with others in place, but the point is that you can’t optimize what you don’t monitor and manage, and the promise of AI is such that we should be thoughtful about how we govern its adoption across an organization.

Wrapping Up

I hope the ideas were worth considering. For more on my thoughts on AI in particular, my articles Exploring Artificial Intelligence and Bringing AI to the End User can provide some perspective for those who are interested.

Thanks for spending the time to read them. Feedback is welcome as always.

-CJG 03/17/2025