It ought to be easier (and cheaper) to run a business than this…

Complexity and higher than desirable operating cost are prevalent in most medium- to large-scale organizations. With that, generally some interest follows in exploring ways to reduce and simplify the technology footprint, to reduce ongoing expenses, mitigate risk and limit security exposure, and free up capital either to reinvest in more differentiated and value-added activity, or to contribute directly to the bottom line overall.

The challenge is really in trying to find the right approach to simplification that is analytically sound while providing insight at speed so you can get to the work and not spend more time “analyzing” than is required at any step of the process.

In starting to outline the content for this article, aside from identifying the steps in a rationalization process and working through a practical example to illustrate some scenarios that can occur, I also started noting some other, more intangible aspects to the work that have come up in my experience. When that list reached ten different dimensions, I realized that I needed to split what was intended to be a single article on this topic into two parts: one that addresses the process aspects of simplification and one that addresses the more intangible and organizational/change management-oriented dimensions. This piece is focused on the intangibles, because the environment in which you operate is critical to setting the stage for the work and ultimate results you achieve.

The Remainder of this Article…

The dimensions that came to mind fell into three broader categories, into which they are organized below, they are:

- Leading and Managing Change

- Guiding the Process and Setting Goals

- Planning and Governance

For each dimension, I’ll try to provide some perspective on why it matters and some potential ideas to consider in the interest of addressing them in the context of a simplification effort overall.

Leading and Managing Change

At its core, simplification is a change management and transformational activity and needs to be approached as such. It is as much about managing the intangibles and maintaining healthy relationships as anything to do with the process you follow or opportunities you surface. Certainly, the structural aspects and the methodology matter, but without giving attention to the items below, likely you will have either some very rough sledding in execution, suboptimize your outcomes, or fail altogether. Said differently: the steps you follow are only part of the work, improving your operating environment is critically important.

Leadership and Culture Matter

Like anything else that corresponds to establishing excellence in technology, courageous leadership and an enabling culture are fundamental to a simplification activity. The entire premise associated with this work rests in change and, wherever change is required, there will be friction and resistance, and potentially significant resistance at that.

Some things to consider:

- Putting the purpose and objective of the change front and center and reinforcing it often (likely reducing operating expense in the interest of improving profitability or freeing up capital for discretionary spending)

- Working with a win-win mindset, looking for mutual advantage, building partnerships, listening with empathy, and seeking to enroll as many people in the cause as possible over time

- Being laser-focused on impact, not solely on “delivery”, as the outcomes of the effort matter

- Remaining resilient, humble (to the extent that there will be learnings along the way), and adaptable, working with key stakeholders to find the right balance between speed and value

It’s Not About the Process, It’s About Your Relationships

Much like portfolio management, it is easy to become overly focused on the process and data with simplification work and lose sight of the criticality of maintaining a healthy business/technology partnership. If IT has historically operated in an order taker mode, suggesting potentially significant changes to core business applications that involve training large numbers of end users (and the associated productivity losses and operating disruptions that come with that) may go nowhere, regardless of how analytically sound your process is.

Some things to consider:

- Know and engage your customer. Different teams have different needs, strategies, priorities, risk tolerance, and so on

- You can gather data and analyze your environment (to a degree) independent of your business partners, but they need to be equally invested in the vision and plan for it to be successful

- Establishing a cadence, individually and collectively, with key stakeholders, aligned to the pace of the work, minimally to maintain a healthy, transparent, and open dialogue on objectives, opportunities, risks, and required inventions and support, is important

Be a Historian as Much as You are an Auditor

Back to the point above on improving the operating environment being as important as your process/ methodology, it is important to recognize something up front in the simplification process: you need to understand how you got where you are as part of the exercise, or you may end right back there as you try to make things “better”. It could be that complexity is a result of a sequence of acquisitions, a set of decentralized decisions without effective oversight or governance, functional or capability gaps in enterprise solutions being addressed at a “local” level, underlying culture or delivery issues, etc. Knowing the root causes matters.

As an example, I once saw a situation where two teams implemented different versions of the same application (in different configurations) purely because the technology leaders didn’t want to work with each other. The same application could’ve supported both organizations, but the decisions were made without enterprise-level governance, the operating complexity and TCO increased, and the subsequent cost to consolidate into a single instance was deemed “lower priority” than continuing work. While this is a very specific example, the point is that understanding how complexity is created can be very important in pivoting to a more streamlined environment.

Some things to consider:

- As part of the inventory activity, look beyond pure data collection to having an opportunity to understand how the various portfolios of applications came about over time, the decisions that led to the complexity that exists, the pain points, and what is viewed as working well (and why)

- Use the insights obtained to establish a set of criteria to consider in the formation of the vision and roadmap for the future so you have a sense whether the changes you’re making will be sustainable. These considerations could also help identify risks that could surface during implementation that could reintroduce the kind of complexity in place today

What Defines “Success”

Normally, a simplification strategy is based on a snapshot of a point in time, with an associated reduction in overall cost (or shift in overall spend distribution) and/assets (applications, data solutions, etc.). This is generally a good way to establish the case for change and desired outcome of the activity itself, but it doesn’t necessarily cover what is “different” about the future state beyond a couple core metrics. I would argue that it is also important to consider what I mentioned in the previous point, which is how the organization developed a complex footprint to begin with.

As an example, if complexity was caused by a rapid series of acquisitions, even if I do a good job of reducing or simplifying the footprint in place, if I continue to acquire new assets, I will end up right back where I was, with a higher operating cost than I’d like. In this case, part of your objective could be to have a more effective process for integrating acquisitions.

Some things to consider:

- Beyond the financial and operating targets, identify any necessary process or organizational changes needed to facilitate sustainability of the environment overall

- This could involve something as simple as reviewing enterprise-level governance processes, or more structural changes in how the underlying technology footprint is managed

Guiding the Process and Setting Goals

A Small Amount of Good Data is Considerably Better than a Lot of Bad

As with any business situation, it’s tempting to assume that having more data is automatically a good thing. In the case of maintaining an asset inventory, the larger and more diverse an organization is, the more difficult it is to maintain the data with any accuracy. To that end, I’m a very strong believer in maintaining as little information as possible, doing deep dives into detail only as required to support design-level work.

As an example, we could start the process by identifying functional redundancies (at a category/component level) and spend allocations within and across portfolios as a means to surface overall savings opportunity and target areas for further analysis. That requires a critical, minimum set of data, but at a reasonable level of administrative overhead. Once specific target areas are identified and prioritized, further data gathering in the interest of comparing different solutions, performing gap analyses, and identifying candidate future state solutions can be done as a separate process. This approach is prioritizing going broad (to Define opportunities) versus going deep (to Design the solution), and I would argue it is a much more effective and efficient way to go about simplification, especially if the underlying footprint has any level of volatility where the more detailed information will become outdated relatively quickly.

Some things to consider:

- Prioritize a critical, minimum set of data (primary functions served by an application, associated TCO, level of criticality, businesses/operating units supported, etc.) to understand spend allocation in relation to the operating and technology footprint

- Deep dive into more particulars (functional differences across similar systems within a given category) as part of a specific design activity downstream of opportunity identification

Be Greedy, But Realistic

The simplification process is generally going to be iterative in nature, insofar as there may be a conceptual target for complexity and spend reduction/reallocation at the outset, some analysis is performed, the data provides insight on what is possible, the targets are adjusted, further analysis or implementation is performed, the picture is further refined, and so on.

In general, my experience is that there are always going to be issues in what you can practically pursue, and therefore, it is a good idea to overshoot your targets. By this, I mean that we should strive to identify more than our original savings goals because if we limit the level of opportunities we identify to a preconceived goal or target, we may either suboptimize the business outcome if things go well, or fall short of expectations in the event we are able to pursue only a subset of what is originally identified for various business, technology, or implementation-related issues.

Some things to consider:

- Review opportunities, asking what would be different if you could only pursue smaller, incremental efforts, had a target that was twice what you’ve identified, could start from scratch and completely redefine your footprint with an “optimal case” in mind… and consider what, if anything would change about your scope and approach

Planning and Governance

Approach Matters

Part of the challenge with simplification is knowing where to begin. Do you cover all of the footprint, the fringe (lower priority assets), the higher cost/core systems? The larger an organization is, the more important it is to target the right opportunities quickly in your approach and not try to boil the ocean. That generally doesn’t work.

I would argue that the primary question to understand in terms of targeting a starting point is where you are overall from a business standpoint. The first iteration of any new process tends to generate learnings and improvements, so there will be more disruption than expected the first time you execute the process end-to-end. To that point, if there is a significant amount of business risk to making widespread, foundational changes, it may make sense to start on lower risk, clean up type activities on non-core/supporting applications (e.g., Treasury, Tax, EH&S, etc.) by comparison with core solutions (like an ERP, MES, Underwriting, Policy Admin, etc.). On the other hand, if simplification is meant to help streamline core processes, enable speed-to-market and competitive advantage, or some form of business growth, it could be that focusing on core platforms first is the right approach to take.

The point is that the approach should not be developed independent of the overall business environment and strategy, they need to align with each other.

Some things to consider:

- As part of the application portfolio analysis, understand the business criticality of each application, level of planned changes and enhancements, how those enable upcoming strategic business goals, etc.

- Consider how the roadmap will enable business outcomes over time; whether that is ideally a slow, build process of incremental gains, or more of a big bets, high impact changes that materially affect business value and IT spend

Accuracy is More Important Than Precision

This point may seem to contradict what I wrote earlier in terms of having a smaller amount of good data, but the point here is that it’s important to acknowledge in a transformation effort that there is a directly proportional relationship between the degree of change involved in the effort and the associated level of uncertainty in the eventual outcome. Said differently: the more you change, the less you can predict the result with any precision.

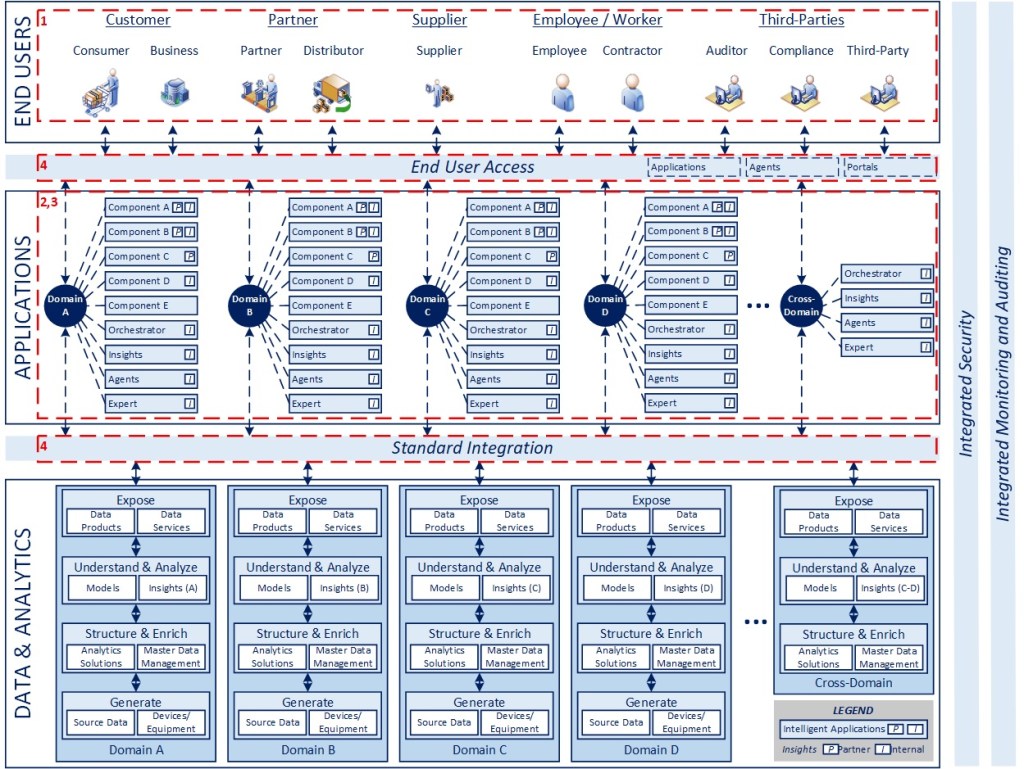

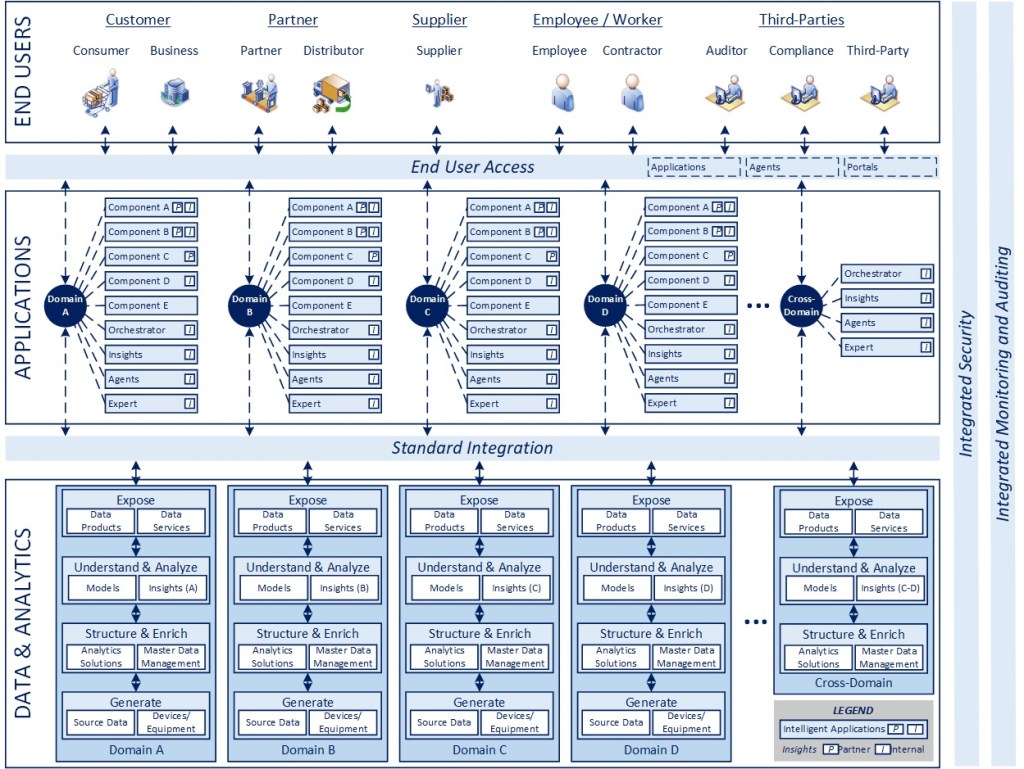

This is true because there is a limited level of data generally available in terms of the operating impact of changes to people, process, and technology. Consequently, the more you change in terms of one or more of those elements, your ability to predict the exact outcome from a metrics standpoint (beyond a more anecdotal/conceptual level) will be limited. In line with the concepts that I shared in the recent “Intelligent Enterprise 2.0” series, with orchestration and AI, I believe we can gather, analyze, and leverage a greater base of this kind of data, but the infrastructure to do this largely doesn’t exist in most organizations I’ve seen today.

Some things to consider:

- Be mindful not to “overanalyze” the impact of process changes up front in the simplification effort. The business case will generally be based on the overall reduction in assets/ complexity, changes in TCO, and shifts (or reductions) in staffing levels from the current state

- It is very difficult to predict the end state when a large number of applications are transitioned as part of a simplification program, so allow for a degree of contingency in the planning process (in schedule and finances) rather than spending time. Some things that may not appear critical generally will reveal themselves to be only in implementation, some applications that you believe you can decommission will remain for a host of reasons, and so on. The best laid plans on paper rarely prove out exactly in the course of execution depending on the complexity of the operating environment and culture in place

Expect Resistance and Expect a Mess

Any large program in my experience tends to go through an “optimism” phase, where you identify a vision and fairly significant, transformative goal, the business case and plan looks good, it’s been vetted and stakeholders are aligned, and you have all the normal “launch” related events that generate enthusiasm and momentum towards the future… and then reality sets in, and the optimism phase ends.

Having written more than once on Transformation, the reality is that it is messy and challenging, for a multitude of reasons, starting with patience, adaptability, and tenacity it takes to really facilitate change at a systemic level. Status quo feels safe and comforting, it is known, and upsetting that reality will necessarily lead to friction, resistance, and obstacles throughout the process.

Some things to consider:

- Set realistic goals for the program at the outset, acknowledge that it is a journey, that sustainable change takes time, the approach will evolve as you deliver and learn, and that engagement, communication, and commitment are the non-negotiables you need throughout to help inform the right decisions at the right time to promote success

- Plan with the 30-, 60-, and 90-day goals in mind, but acknowledge that any roadmap beyond the immediate execution window will be informed by delivery and likely evolve over time. I’ve seen quite a lot of time wasted on detailed planning more than one year out where a goal-based plan with conceptual milestones would’ve provided equal value from a planning and CBA standpoint

Govern Efficiently and Adjust Responsively

Given the scale and complexity of simplification efforts, it would be relatively easy to “over-report” on a program of this type and cause adverse impact on the work itself. In line with previous articles that I’ve written on governance and transparency, my point of view is that the focus needs to be on enabling delivery and effective risk management, not administrative overhead.

Some things to consider:

- Establish a cadence for governance early on to review ongoing delivery, identify interventions and support needed, learnings that can inform future planning, and adjust goals as needed

- Large programs succeed or fail in my experience based on maintaining good transparency to where you are, identifying course corrections when needed, and making those adjustments quickly to minimize the cost of “the turns” when they inevitably happen. Momentum is so critical in transformation efforts that minimizing these impacts is really important to keeping things on track

Wrapping Up

Overall, the reason for separating the process from the change in addressing simplification was deliberate, because both aspects matter. You can have a thoughtful, well executed process and accomplish nothing in terms of change and you can equally be very mindful of the environment and changes you want to bring about, but the execution model needs to be solid, or you will lose any momentum and good will you’ve built in support of your effort.

Ultimately, recognizing that you’re both engaging in a change and a delivery activity is the critical takeaway. Most medium- to large-scale environments end up complex for a host of reasons. You can change the footprint, but you need to change the environment as well, or it’s only a matter of time before you’ll find yourself right back where you started, perhaps with a different set of assets, but a lot of same problems you had in the first place.

I hope the ideas were worth considering. Thanks for spending the time to read them. Feedback is welcome as always.

-CJG 10/22/2025