When looking towards the Delivering at Speed dimension of Excellence by Design, it’s worthwhile to understand roles and responsibilities and, more importantly, the criticality of effective communication and collaboration in delivery. To that end, I wanted to provide a quick commentary on the value and risk of RACI as an enabler in the process.

Many who have worked with me know that I’m not a fan of the RACI tool. In this article, I’ll cover what I consider good and not so good about it. Hopefully the concepts will be helpful.

At the end of the day, what makes teams effective is a collective investment in success. That takes courage and a willingness to do whatever it takes to deliver, particularly if a project is complex or high risk. Where individuals and teams don’t lean into that discomfort, things can easily become imbalanced, inefficient, and ineffective… and the opportunity for excellence is lost. The ultimate reality is that technology delivery is messy and complex, it involves dealing with adversity and is not for the faint of heart, which is why courageous leadership is the first and most critical dimension to driving excellence in an organization.

A Quick Refresher

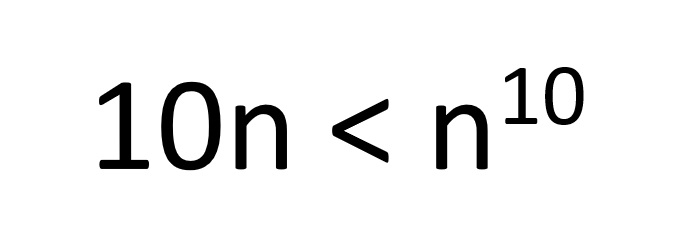

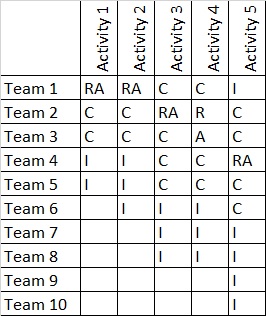

For those who may be unfamiliar, the RACI tool is used to help clarify roles and responsibilities across a set of constituents against a defined set of activities, deliverables, or whatever is relevant to the conversation.

The process is generally to have a facilitator populate a grid in two dimensions, with stakeholders or teams as a set of rows and the activities or deliverables across an entire project lifecycle (as an example) as the columns. Once the teams and work are clarified, the team then typically goes a column at a time, noting which teams have which responsibilities using the RACI notation to indicate who is:

- R – Responsible (DOER – primarily responsible for performing the activity)

- A – Accountable (LEADER – ultimately accountable for the execution)

- C – Consulted (ADVISOR – asked to provide input, in a supporting role)

- I – Informed (LISTENER – notified of the status or outcome, but not involved)

A conceptual example of a completed RACI chart could look something like this:

Generally, there should only be one “Accountable” party per activity, though there can be more than one individual or team “Responsible” for performing the work. In many cases, “R” and “A” go together, though there can be situations where someone is playing a general contractor-type role who is Accountable, but someone else is actually playing a subcontracting-type role who is Responsible for performing the work. In one of my previous employers, we occasionally collapsed the “R” and “A” categories into a single “Owner” (O) role, which indicated the individual or team who was both responsible and accountable and simplified the facilitation of the exercise.

What’s Good about RACI

In my experience, the value of a RACI discussion is in the conversation, not the tool.

The conversation is helpful in two primary respects:

- Clarifying the scope and breadth of activities/ deliverables/ responsibilities that are associated with whatever the cross-functional team is trying to accomplish

- Having an understanding of the anticipated interactions of that cross-functional team against those activities

On the latter point, the exercise can be particularly helpful for a newly formed team or on a new type of effort where the combination of activities is emerging and the interactions across the team against those activities isn’t clearly understood.

The discussion itself gives the team a chance to engage, interact, experience the various communication and leadership styles and, in the process, talk about the work they need to perform.

Where Things Go Awry

…So what’s the problem?

Well, the problem is sometimes in the mindset of the participants as they enter the discussion and how the tool is ultimately used in practice.

Things to watch for in a RACI discussion:

- Asserting Control / Promoting Exclusion

- There are times when participants use the tool and process as a way to establish their authority to make decisions (as the “Accountable” party) in a way that excludes others

- In these cases, the RACI tool can become a hammer that enables dysfunction and empowers poor leadership

- Showing a Lack of Accountability

- There are times when the tone of discussion shifts towards an “us” and “them” conversation and the concept of “team” is subjugated to who is accountable if something goes wrong.

- In this situation, the tool becomes a hammer to assign blame and undermine partnership

- Encouraging a Lack of Collaboration

- Finally, the stronger the contrast between “RA” and “C” comes across, there is risk of an underlying level of dysfunction that goes beyond activities and deliverables

- While the tool and process are meant to help foster healthy discussion on primary accountability and roles, an extreme version of its use can feel like there is a lot of “throwing things over the wall”… and that is normally something you can hear in the discussion itself

Summing this up, while RACI can be a useful tool, it can also be a mechanism to stratify dysfunction in an organization, enable poor leadership, assign blame, and do more harm than good.

Breaking Down the Model

In thinking about the above, the question arises: “Ok, so what do you do about it?”

In a previous employer where we conducted a lot of client workshops, we would start with a predefined set of ground rules and allow the clients to add to the list as they saw fit. Depending on the group assembled, there were times when that flexibility actually would go astray and the rules became a long, laundry list of “what not to dos”.

If the discussion started to feel unhealthy, we would suggest that we reset the list back to two things:

- Do what makes sense

- Do the right thing

In practice, almost any situation that would arise in a workshop setting could be addressed with those two principles and they are simple and broad enough that they cover what you need to facilitate a session on about any topic.

Going back to RACI, when the discussions go astray, the same type of principles may be helpful to set the tone for collaboration as part of the effort.

Summing It Up

Stepping back from the tools and process, the critical point to remember is the importance of communication and collaboration in a cross-functional team.

In my experience, when people are effective collaborators and the underlying relationships are sound, there isn’t a need for RACI discussions. People work past boundaries, sometimes swap responsibilities where the capabilities of individuals are roughly equivalent, and the team is focused less on “who owns what” and doing what they need to do to meet the conditions of success. There is a mindset of mutual support and partnership… and the efficiency of the execution will be much higher by extension.

Most of the time, when I hear someone request or suggest a RACI discussion, I assume there is an underlying issue or source of dysfunction. It doesn’t mean the conversations can’t be useful in helping to surface and address those concerns and challenges, but it is important to understand they are not a cure all if the outcome is just a snapshot of something that wasn’t working effectively in the first place.

Hopefully the concepts were helpful. As always, feedback is welcome and appreciated.

-CJG 06/06/2022