Context

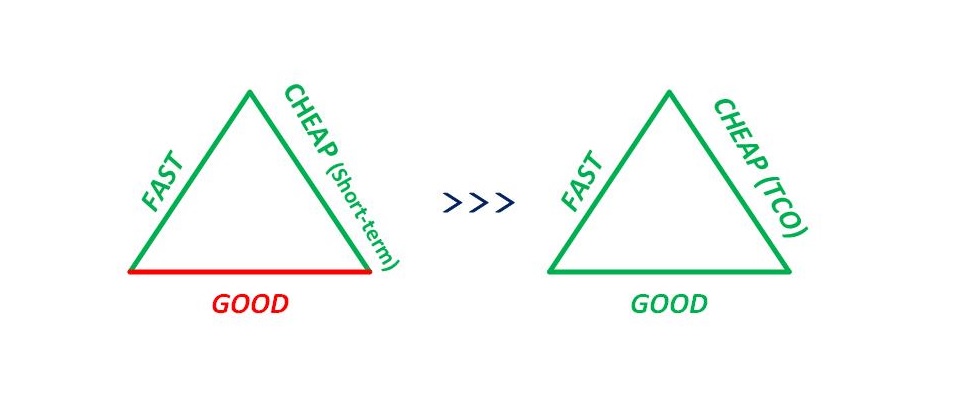

In my article on Excellence by Design, the fifth dimension I reference is “Delivering at Speed”, basically understanding the delicate balance to be struck in technology with creating value on a predictable, regular basis while still ensuring quality.

One thing that is true is software development is messy and not for the faint of heart or risk averse. The dynamics of a project, especially if you are doing something innovative, tend to be in flux at a level that requires you to adapt on the fly, make difficult decisions, accept tradeoffs, and abandon the idea that “perfection” even exists. You can certainly try to design and build out an ivory tower concept, but the probability is that you’ll never deliver it or, in the event you do, that it will take you so long to make it happen that your solution will be obsolete by the time you finally go live.

To that end, this article is meant to share a set of delivery stories from my past. In three cases, I was told the projects were “impossible” or couldn’t be delivered at the outset. In the other two, the level of complexity or size of the challenge was relatively similar, though they weren’t necessarily labeled “impossible” at any point. In all cases, we delivered the work. What will follow, in each case, are the challenges we faced, what we did to address them, and what I would do differently if the situation happened again. Even in success, there is ample opportunity to learn and improve.

Looking across these experiences, there is a set of things I would say apply in nearly all cases:

- Commitment to Success

- It has to start here, especially with high velocity or complex projects. When you decide you’re going to deliver day one, every obstacle is a problem you solve, and not a reason to quit. Said differently, if you are continually looking for reasons to fail, you will.

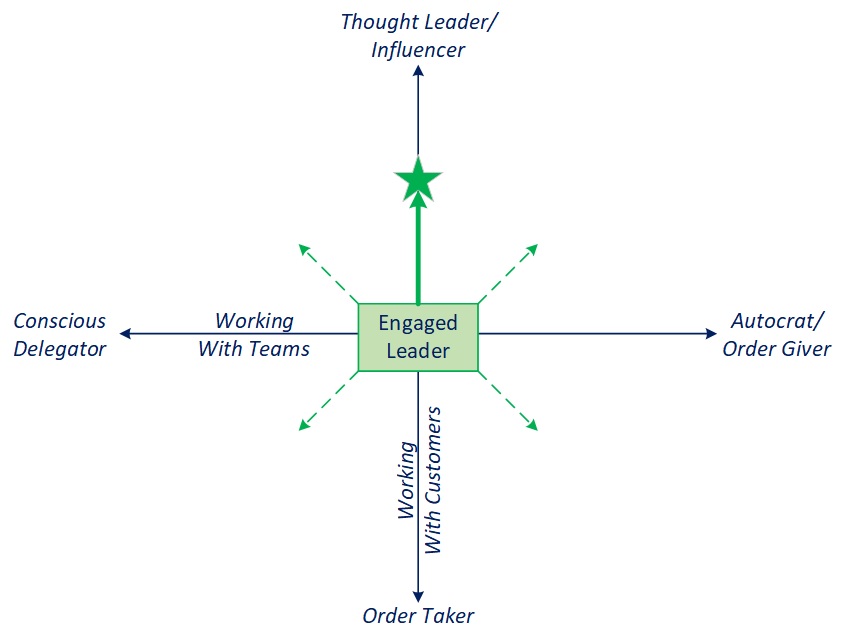

- Adaptive Leadership

- Change is part of delivering technology solutions. Courageous leadership that embraces humility, accepts adversity, and adapts to changing conditions will be successful far more than situations where you hold onto original assumptions beyond their usefulness

- Business/Technology Collaboration

- Effective communication, a joint investment in success, and partnership make a significant difference in software delivery. The relationships and trust it takes can be an achievement in itself, but the quality of the solution and ability to deliver is definitely stronger where this is in place

- Timely Decision Making

- As I discuss in my article On Project Health and Transparency, there are “points of inflection” that occur on projects of any scale. Your ability to respond, pivot, and execute in a new direction can be a critical determinant to delivering

- Allowing for the Unknown

- With any project of scale or reasonable complexity, there will be pure “unknown” (by comparison with “known unknown”) that is part of the product scope, the project scope, or both. While there is always a desire to deliver solutions as quickly as possible with the lowest level of effort (discussed in my article Fast and Cheap Isn’t Good), including some effort or schedule time proactively as contingency for the unknown is always a good idea

- Excessive Complexity

- One thing that is common across most of these situations is that the approach to the solution was building a level of flexibility or capability that probably was beyond what was needed in practice. This is not unusual on new development, especially where significant funding is involved, because those bells and whistles create part of the appeal that justifies the investment to begin with. That being said, if a crawl-walk-run type approach that evolves to a more feature-rich solution is possible, the risk profile for the initial efforts (and associated cost) will likely be reduced substantially. Said differently, you can’t generate return on investment for a solution you never deliver

The remainder of this article is focused on sharing a set of these delivery stories. I’ve purposefully reordered and made them a bit abstract in the interest of maintaining a level of confidentiality on the original efforts involved. In practice, these kinds of things happen on projects all the time, the techniques referenced are applicable in many situations, and the specifics aren’t as important.

Delivering the “Impossible”

Setting the Stage

I’ll always remember how this project started. I had finished up my previous assignment and was wondering what was next. My manager called me in and told me about a delivery project I was going to lead, that it was for a global “shrink wrap” type solution, that a prototype had been developed, that I needed to design and build the solution… but not to be too concerned because the timeframe was too short, the customer was historically very difficult to work with, and there was “no way to deliver the project on time”. Definitely not a great moment for motivating and inspiring an employee, but my manager was probably trying to manage my expectations given the size of the challenge ahead.

Some challenges associated with this effort:

- The nature of what was being done, in terms of automating an entirely manual process had never been done before. As such, the requirements didn’t exist at the outset, beyond a rudimentary conceptual prototype that demonstrated the desired user interface behavior

- I was completely unfamiliar with the technology used for the prototype and needed to immediately assess whether to continue forward with it or migrate into a technology I knew

- The timeframe was very aggressive and the customer was notorious for not delivering on time

- We needed everything we developed to fit on a single 3.5-inch diskette for distribution, and it was not a small application to develop

What Worked

Regardless of any of the mechanics, having been through a failed delivery early in my career, my immediate reaction to hearing the project was doomed from the outset was that there was no way we were going to allow that to happen.

Things that mattered in the delivery:

- Within the first two weeks, I both learned the technology that was used for the prototype and was able to rewrite it (it was a “smoke and mirrors” prototype) into a working, functional application. Knowing that the underlying technology could do what was needed in terms of the end user experience, we took the learning curve impact in the interest of reducing the development effort that would have been required to try and create a similar experience using other technologies we were using at the time

- Though we struggled initially, eventually we brought a leader from the customer team to our office to work alongside us (think Agile before Agile) so we could align requirements with our delivery iterations and produce application sections for testing in relatively complete form

- We had to develop everything as compact as possible given the single disk requirement so the distribution costs wouldn’t escalate (10s of thousands of disks were being shipped globally)

All of the above having helped, the thing that made the largest difference was the commitment of the team (ultimately me and three others) to do whatever was required to deliver. The brute force involved was substantial, and we worked increasing hours, week-after-week, until we pulled seven all night sessions in the last ten days leading up to shipping the software to the production company. It was an exceptionally difficult pace to sustain, but we hit the date, and the “impossible” was made possible.

What I Would Change

While there is a great deal of satisfaction that comes from meeting a delivery objective, especially an aggressive one, there are a number of things I would have wanted to do differently in retrospect:

- We grew the team over time in a way that created additional pressure in the latter half of the project. Given we started with no requirements and were doing something that had never been done, I’m not sure how we could have estimated the delivery to know we needed more help sooner, but minimally, from a risk standpoint, there was too much work spread too thinly for too long, and it made things very challenging later on to catch up

- As I mentioned above, we eventually transitioned to have an integrated business/technology team that delivered the application with tight collaboration. This should have happened sooner, but we collectively waited until it became a critical issue before it escalated to a level than anyone really addressed it. That came when we actually ran out of requirements late one night (it was around 2am) to the point that we needed to stop development altogether. The friction this created between the customer and development team was difficult to work through and is something the change in approach made much better, just too late in the project

- From a software standpoint, given it was everyone on the team’s first foray into new technology (starting with me), there was a lot we could have done to design the solution better, but we were unfortunately learning on the job. This is another one that I don’t know how we could have offset, beyond bringing in an expert developer to help us work through the design and sanity check our work, but it was such new technology at the time, that I don’t know that was really a viable option or that such expertise was available

- This was also my first global software solution and I didn’t appreciate the complexities of localization enough to avoid making some very basic mistakes that showed up late in the delivery process.

Working Outside the Service Lines

Setting the Stage

This project honestly was sort of an “accidental delivery”, in that there was no intention from a services standpoint to take on the work to begin with. Similar to my product development experience, there was a customer need to both standardize and automate what was an entirely manual process. Our role, and mine in particular, was to work with the customer, understand the current process across the different people performing it, then look for a way to both standardize the workflow itself (in a flexible enough way that everyone could be trained and follow that new process), then to define the opportunities to automate it such that a lot of the effort done in spreadsheets (prone to various errors and risks) could be built into an application that would make it much easier to perform the work.

The point of inflection came when we completed the process redesign and, with no implementation partner in place (and no familiarity with the target technologies in the customer team), the question became “who is going to design and build this solution?” Having a limited window of time, a significant amount of seasonal business that needed to be processed, and the right level of delivery experience, I offered to shift from a business analyst to the technology lead on the project. With a substantial challenge ahead, I was again told what we were trying to do could never be done in the time we had. Having had previous success in that situation, I took it as a challenge to figure out what we needed to do to deliver.

Some challenges associated with this effort:

- The timeframe was the biggest challenge, given we had to design and develop the entire application from scratch. The business process was defined, but there was no user interface design, it was built using relatively new technology, and we needed to provide the flexibility users were used to having in Excel while still enforcing a new process

- Given the risk profile, the customer IT manager assumed the effort would fail and consequently provided only a limited amount of support and guidance until the very end of the project, which created some integration challenges with the existing IT infrastructure

- Finally, given that there were technology changes occurring in the market as a whole, we encountered a limitation in the tools (given the volume of data we were processing) that nearly caused us to hit a full stop mid-development

What Worked

Certainly, an advantage I had coming into the design and delivery effort was that I helped develop the new process and was familiar with all the assumptions we made during that phase of the work. In that respect, the traditional disconnect between “requirements” and “solution” was fairly well mitigated and we could focus on how to design the interface, not the workflow or data required across the process.

Things that mattered in the delivery:

- One major thing that we did well from the outset was work in a prototype-driven approach, engaging with the end customer, sketching out pieces of the process, mocking them up, confirming the behavior, then moving onto the next set of steps while building the back end of the application offline. Given we only had a matter of months, the partnership with the key business customer and their investment in success made a significant difference in the efficiency of our delivery process (again, very Agile before Agile)

- Despite the lack of support from customer IT leadership standpoint, a key member of their team invested in the work, put in a tremendous amount of effort, and helped keep morale positive despite the extreme hours we worked for essentially the entire duration of the project

- While not as pleasant, another thing that contributed to our success was managing performance actively. Wanting external expertise (and needing the delivery capacity), we pulled in additional contracting help, but had inconsistent experience with the commitment level of the people we brought in. Simply said: you can’t deliver high velocity project with a half-hearted commitment. It doesn’t work. The good news is that we didn’t delay decisions to pull people where the contributions weren’t where they needed to be

- On the technology challenges, when serious issues arose with our chosen platform, I took a fairly methodical approach to isolating and resolving the infrastructure issues we had. The result was a very surgical and tactical change to how we deployed the application without needing to do a more complex (and costly) end user upgrade that initially appeared to be our only option

What I Would Change

While the long hours and months without a day off ultimately enabled us to deliver the project, there were certainly learnings from this effort that I took away despite our overall success.

Things I would have wanted to do differently in retrospect:

- While the customer partnership was very effective overall, one area that where we didn’t engage early enough was with the customer analytics organization. Given the large volume of data, heavy reliance on computational models, and the capability for users to select data sets to include in the calculations being performed, we needed more support than expected to verify our forecasting capabilities were working as expected. This was actually a gap in the upstream process design work itself, as we identified the desired capability (the “feature”) and where it would occur within the workflow, but didn’t flesh out the specific calculations (the “functionality”) that needed to be built to support it. As a result, we had to work through those requirements during the development process itself, which was very challenging

- From a technology standpoint, we assumed a distributed approach for managing data associated with the application. While this reduced the data footprint for individual end users and simplified some of the development effort, it actually made the maintenance and overall analytics associated with the platform more complex. Ultimately, we should have centralized the back end of the application. This is something that was done subsequent to the initial deployment, though I’m not certain if we would have been able to take that approach with the initial release and still made the delivery date

- From a services standpoint, while I had the capability to lead the design and delivery of the application, the work itself was outside the core service offerings of our firm. Consequently, while we delivered for the customer, there wasn’t an ability to leverage the outcome for future work, which is important in consulting in building your business. In retrospect, while I wouldn’t have learned and gotten the experience, we should have engaged a partner in the delivery and played a different role in implementation

Project Extension

Setting the Stage

Early in my experience of managing projects, I had the opportunity to take on an effort where the entire delivery team was coming off a very difficult, long project. I was motivated and wanted to deliver, everyone else was pretty tired. The guidance I received at the outset was not to expect very much, and that the road ahead was going to be very bumpy.

Some challenges associated with this effort:

- As I mentioned above, the largest challenge was a lack of motivation, which was a strength in other high pressure deliveries I’d encountered before. I was unused to dealing with it from a leadership standpoint and didn’t address it as effectively as I should have

- From a delivery standpoint, the technical solution was fairly complex, which made the work and testing process challenging, especially in the timeframe we had for the effort

- At a practical level, the team was larger than I had previous experience leading. Leading other leaders wasn’t something I had done before, which led me to making all the normal mistakes that comes with doing so for the first time, which didn’t help on either efficiency or sorely needed motivation

What Worked

While the project started with a team that was already burned out, the good news is that the base application was in place, the team understood the architecture, and the scope was to buildout existing capabilities on top of a reasonably strong foundation. There was a substantial amount of work to be performed in a relatively short timeframe, but the good news is that we weren’t starting from scratch and there was recent evidence that the team could deliver.

Things that mattered in the delivery:

- The client partnership was strong, which helped both in addressing requirements gaps and, more importantly, in performing customer testing in both an efficient and effective manner given the accelerated timeframe

- At the outset of the effort, we revisited the detailed estimates and realigned the delivery team to balance the work more effectively across sub-teams. While this required some cross-training, we reduced overall risk in the process

- From a planning standpoint, we enlisted the team to try out an aggressive approach where we set all the milestones slightly ahead of their expected delivery date. Our assumption was that, by trying to beat our targets, we could create some forward momentum that would create “effort reserve” to use for unexpected issues and defects later in the project

- Given the pace of the work and size of the delivery team, we had the benefit of strong technical leads who helped keep the team focused and troubleshoot issues as and when we encountered them

What I Would Change

Like other projects I’m covering in this article, the team put in the effort to deliver on our commitments, but there were definitely learnings that came through the process.

Things I would have wanted to do differently in retrospect:

- Given it was my first time leading a larger team under a tight timeline, I pushed where I should have inspired. It was a learning experience that I’ve used for the benefit of others many times since. While I don’t know what impact it might have had on the delivery itself, it might have made the experience of the journey better overall

- From a staffing standpoint, we consciously stuck to the team that helped deliver the initial project. Given the burnout was substantial and we needed to do a level of cross-training anyway, it might have been a good idea for us to infuse some outside talent to provide fresh perspective and much needed energy from a development standpoint

- Finally, while it was outside the scope of work itself, this project was an example of a situation I’ve encountered a few times over the years where the requirements of the solution and its desired capabilities were overstated and translated into a lot of complexity in architecture and design. My guess is that we built a lot of flexibility that wasn’t required in practice

Modernization Program

Setting the Stage

What I think of as another “impossible” delivery came with a large-scale program that started off with everyone but the sponsors assuming it would fail.

Some challenges associated with this effort:

- The largest thing stacked against us was two failed attempts to deliver the project in the past, with substantial costs associated with each. Our business partners were well aware of those failures, some having participated in them, and the engagement was tentative at best when we started to move into execution

- We also had significant delivery issues with our primary technology partner that resulted in them being transitioned out mid-implementation. Unfortunately, they didn’t handle the situation gracefully, escalated everywhere, told the CIO the project would never be successful, and the pressure on the team to hit the first release on schedule was increased by extension

- From an architecture standpoint, the decision was made to integrate new technology with existing legacy software wherever possible, which added substantial development complexity

- The scale and complexity for a custom development effort was very significant, replacing multiple systems with one new, integrated platform, and the resulting planning and coordination was challenging

- Given the solution replaced existing production systems, there was a major challenge in keeping capabilities in sync between the new application and ongoing enhancements being implemented in parallel by the legacy application delivery team

What Worked

Things that mattered in the delivery:

- As much as any specific decision or “change”, what contributed to the ultimate success of the program was our continuous evolution of the approach as we encountered challenges. With a program of the scale and complexity we were addressing, there was no reasonable way to mitigate the knowledge and requirements risks that existed at the outset. What we did exceptionally well was to pivot and work through obstacles as they appeared… in architecture, requirements, configuration management, and other aspects of the work. That adaptive leadership was critical in meeting our commitments and delivering the platform

- The decision to change delivery partners was a significant disruption mid-delivery that we managed with a weekly transition management process to surface and address risks and issues on an ongoing basis. The governance we applied was very tight across all the touchpoints into the program and it helped us ultimately onboard the new partner and reduce risk on the first delivery date, which we ultimately met

- To accelerate overall development across the program, we created both framework and common components teams, leveraging reuse to help reduce risk and effort required in each of the individual product teams. While there was some upfront coordination to decide how to arbitrate scope of work, we reduced the overall effort in the program substantially and could, in retrospect, have built even more “in common” than we did

- Finally, to keep the new development in sync with the current production solutions, we integrated the program with ongoing portfolio management processes from work-intake and estimation through delivery as if we were already in production. This helped us avoid rework that would have come if we had to retrofit those efforts post-development in the pre-production stage of the work

The net result of a lot of adjustments and a very strong, committed set of delivery teams was that we met our original committed launch date and moved into the broader deployment of the program.

What I Would Change

The learnings from a program of this scale could constitute an article all on their own, so I’ll focus on a subset that were substantial at an overall level.

Things I would have wanted to do differently in retrospect:

- As I mentioned in the point on common components above, the mix between platform and products wasn’t right. Our development leadership was drawn from the legacy systems, which helped, given they were familiar with the scope and requirements, but the downside was that the new platform ended up being siloed in a way that mimicked the legacy environment. While we started to promote a culture of reuse, we could have done a lot more to reduce scope in the product solutions and leverage the underlying platform more

- Our product development approach should have been more framework-centric, being built towards broader requirements versus individual nuances and exceptions. There was a considerable amount of flexibility architected into the platform itself, but given the approach was focused on implementing every requirement as if it was an exception, the complexity and maintenance cost of the resulting platform was higher than it should have been

- From a transition standpoint, we should have replaced our initial provider earlier, but given the depth and nature of their relationships and a generally risk-averse mindset, we gave them a matter of months to fail, multiple times, before making the ultimate decision to change. Given there was a substantial difference in execution once we completed transition, we waited longer than we should have

- Given we were replacing multiple existing legacy solutions, there was a level of internal competition that was unhealthy and should have been managed more effectively from a leadership standpoint. The impact was that there were times the legacy teams were accelerating capabilities on systems we knew were going to be retired in what appeared to be an effort to undermine the new platform

Project Takeover

Setting the Stage

We had the opportunity in consulting to bid on a development project from our largest competitor that was stopped mid-implementation. As part of the discovery process, we received sample code, testing status, and the defect log at the time the project was stopped. We did our best to make conservative assumptions on what we were inheriting and the accuracy of what we received, understanding we were in a bidding situation and had to lean into discomfort and price the work accordingly. In practice, the situation we took over was far worse than expected.

Some challenges associated with this effort:

- While the quality of solution was unknown at the outset, we were aware of a fairly high number of critical defects. Given the project didn’t complete testing and some defects were likely to be blocking the discovery of others, we decided to go with a conservative assumption that the resulting severe defect count could be 2x the set reported to us. In practice the quality was far worse and there were 6x more critical defects than were reported to us at the bidding stage

- In concert with the previous point, while the testing results provided a mixed sense of progress, with some areas being in the “yellow” (suggesting a degree of stability) and others in the “red” (needing attention), in practice, the testing regimen itself was clearly not thorough and there wasn’t a single piece of the application that was better than a “red” status, most of them more accurately “purple” (restart from scratch), if such a condition even existed.

- Given the prior project was stopped, there was a very high level of visibility, and the expectation to pick up and use what was previously built was unrealistic to a large degree, given the quality of work was so poor

- Finally, there was considerable resource contention with the client testing team not being dedicated to the project and, consequently, it became very difficult to verify the solution as we progressed through stabilizing the application and completing development

What Worked

While the scale and difficulty of the effort was largely underrepresented at the outset of the work, as we dug in and started to understand the situation, we made adjustments that ultimately helped us stabilize and deliver the program.

Things that mattered in the delivery:

- Our challenges in testing aside, we had the benefit of a strong client partnership, particularly in program management and coordination, which helped given the high level of volatility we had in replanning as we progressed through the effort

- Given we were in a discovery process for the first half of the project, our tracking and reporting methods helped manage expectations and enable coordination as we continued to revise the approach and plan. One specific method we used was showing the fix rate in relation to the level of undiscovered defects and then mapping that additional effort directly to the adjusted plan. When we visibly accounted for it in the schedule, it helped build confidence that we actually were “on plan” where we had good data and making consistent progress where we had taken on additional, unforeseen scope as well. Those items were reasonably outside our control as a partner, so the transparency helped us given the visibility and pressure surrounding the work was very high

- Finally, we mitigated risk in various situations by making the decision to rewrite versus fix what was handed over at the outset of the project. The code quality being as poor as it was and requirements not being met, we had to evaluate whether it was easier to start over and work with a clean slate versus trying to reverse engineer something we knew didn’t work. These decisions helped us reduce effort and risk, and ultimately deliver the program

What I Would Change

Things I would have wanted to do differently in retrospect:

- As is probably obvious, the largest learning was that we didn’t make conservative enough assumptions in what we were inheriting with the project, the accuracy of testing information provided, or the code samples being “representative” of the entire codebase. In practice, though, had we estimated the work properly and attached the actual cost for doing the project, we might not have “sold” the proposal either…

- We didn’t factor changing requirements into our original estimates properly, partially because we were told the project was mid-testing, and largely built prior to our involvement. This added volatility into the project as we already needed to stabilize the application without realizing the requirements weren’t frozen. In retrospect, we should have done a better job probing on this during the bidding process itself

- Finally, we had challenges maintaining momentum where a dedicated client testing team would have made the iteration process more efficient. It may have been necessary to lean on augmentation or a partner to help balance ongoing business and the project, but the cost of extending the effort was substantial enough that it likely was worth investigating

Wrapping Up

As I said at the outset, having had the benefit of delivering a number of “impossible” projects over the course of my career, I’ve learned a lot about how to address the mess that software development can be in practice, even with disciplined leadership. That being said, the great thing about having success is that it also tends to make you a lot more fearless the next time a challenge comes up, because you have an idea what it takes to succeed under adverse conditions.

I hope the stories were worth sharing. Thanks for spending the time to read them. Feedback is welcome as always.

-CJG 02/07/2023