“Something needs to change… we’re not growing, we’re too slow, we’re not competitive, we need to manage costs…”

Change is an inevitable reality in business. Even the most successful company will face adversity, new competitors, market shifts, evolving customer needs, expense pressures, near-term shareholder expectations, etc. While it’s important to focus on adjusting course and remedying issues, the question is whether you will find yourself in exactly the same (or at least a relatively similar) situation again (along with how quickly) and that comes down to leadership and culture.

Culture issues tend to beget other business issues, whether it’s delayed or misaligned decisions, complacency and a lack of innovation, a lack of collaboration and cooperation, risk averse behaviors, redundant or ineffective solutions, high turnover resulting in lost expertise, and so on. The point is that excellence needs to start “at the top” and work its way throughout an organization, and the mechanism for that proliferation is culture.

The focus of this article will be to explore what it takes to evolve culture in an organization, and to provide ways to think about what can happen when it isn’t positioned or aligned effectively.

It Starts with the Right Intentions

Conformance versus Performance

Before attempting to change anything, the fundamental question to be asked is why you want to have a culture in place to begin with? Certainly, over the course of time and multiple organizations (and clients), I’ve seen culture emphasized to varying degrees, from where it is core to a company’s DNA, to where it is relegated to a poster, web page, or item on everyone’s desk that is seldom noticed or referenced.

In cases where it’s rarely referenced, there is missed opportunity to establish mission and purpose, rallying people around core concepts that can facilitate an effective work environment.

That being said, focusing on culture doesn’t necessarily create a greater good in itself, as I’ve seen environments where culture is used in almost a punitive way, suggesting there are norms to which everyone must adhere and specific language everyone needs to use, or there will be adverse consequences.

That isn’t about establishing a productive work environment, it’s about control and conformance, and that can be toxic when you understand the fundamental issue it represents: employees aren’t trusted enough to do the right thing, be empowered, and enabled to act, so there needs to be a mechanism in place to drive conformity, enforce “common language”, and isolate those who don’t fit the mold to create a more homogenous organizational society.

So, what happens to innovation, diversity, and inclusion in these environments? It’s suppressed or destroyed, because the capabilities and gifts of the individual are lost to the push towards a unified, homogenized whole. That is a fairly extreme outcome of such authoritarian environments, but the point is that a strong culture is not, in itself, automatically good if the focus is control and not performance and excellence.

I’ve written multiple articles on culture and values that I believe are important in organizations, so I won’t repeat those messages here, but the goal of establishing culture should be fostering leadership, innovation, growth, collaboration, and optimizing the contribution of everyone in an organization to serve the greater good. If that doesn’t apply in equal measure to every employee, based on their individual capabilities and experience, that’s fine from my perspective, so long as they don’t detract from the performance of others in the process. The point is that culture isn’t about the words on the wall, it’s about the behaviors that you are aspiring to engender within an organization and the degree to which you live into them every day.

Begin with Leadership

Words and Actions

It is fairly obvious to say that culture needs to start “at the top” and work its way outward, but there are so many issues I’ve seen over time in this step alone, that it is worth repeating.

It is not uncommon for leaders to speak in town hall meetings or public settings and proclaim the merits of the company culture, asking others to follow the core values or principles as outlined, to the betterment of themselves and everyone else (customers and others included as appropriate). Now, the question is: what happens when that person returns to their desk and makes their next set of decisions? This is where culture is measured, and employees notice everything over time.

The challenge for leaders who want excellence and organizational performance is to take culture to heart and do what they can to live into it, even in the most difficult circumstances, which is where it tends to be needed the most. I remember hearing a speaker suggest that the litmus test of the strength of your commitment to culture could be expressed in whether you would literally walk away from business rather than compromise your values. That’s a pretty difficult bar to set in my experience, but an interesting way to think about the choices we make and their relative consequence.

Aligning Incentives versus Values

Building on the previous point, there is a difference between behaviors and values. The latter is what you believe and prioritize, the former is how you act. Behaviors are directly observable; values are indirectly observed through your words and actions.

Why is this important in the context of culture? It is important, because you can incent people in the interest of influencing their behavior, but you can’t change someone’s values, no matter how you incent them. To the extent you want to set up a healthy, collaborative culture and there are individual motivations that don’t align with doing the right thing, organizational performance will suffer in some way, and the more senior the individual(s) are in the organization, the more significant the impact will likely be.

This point ultimately comes down to doing the right level of due diligence during the hiring process, but also being willing to make difficult decisions during the performance management process, because sometimes individual performers with unhealthy behaviors cause a more significant impact than is evident without some level of engagement and scrutiny from a leadership standpoint.

Have a Thoughtful Approach

Incubate -> Demonstrate -> Extend

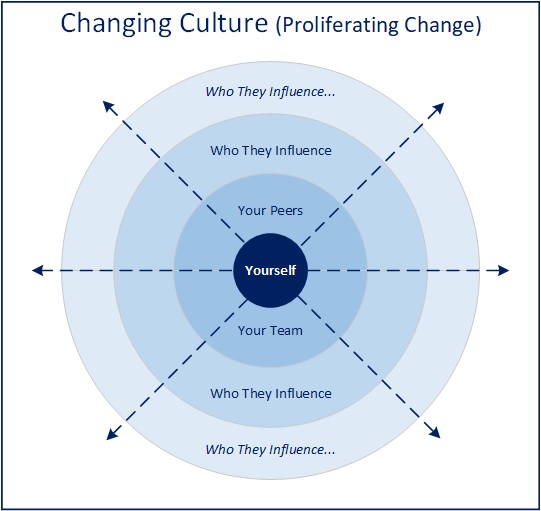

As the diagram above suggests, culture doesn’t change overnight, and being deliberate in the approach to change will have a significant impact to how effective and sustainable it is.

In general, the approach I’d recommend is to start from “center” with leadership, raise awareness, educate on the intent and value to the changes proposed, and incubate there. Broader communication in terms of the proposed shift is likely useful in preparing the next group to be engaged in the process, but the point is to start small, begin “living into” the desired model, evaluating its efficacy, and demonstrating the value it can create, THEN extend to the next (likely adjacent) set of people, and repeat the process over and over until the change has fully proliferated to the entire organization. The length of any given iteration would likely vary depending on the size of the employee population and the degree of change involved (more substantial = longer windows of time), but the point is to be conscious and deliberate in how it is approached so adjustments can be made along the way and to enable leaders to understand and internalize the “right” set of behaviors before expecting them to help advocate and reinforce it in others.

An Example (Building an Architecture Capability)

To provide a simple example, when trying to establish an architecture capability across an organization, it would need to ultimately span from the central enterprise architecture team down to technical leads on individual implementation teams. It would be impractical to implement the model all at once, so it would be more effective to stage it out, working from the top-down, first defining roles and responsibilities across the entire operating model, but then implementing one “layer” of roles at a time, until it is entirely in place.

Since architects are generally responsible for technical solution quality, but not execution, the deployment of the model would need to follow two coordinated paths: building the architecture capability itself and aligning it with the delivery leadership with which it is meant to collaborate and cooperate (e.g., project and program managers). Trying to establish the role without alignment and support from people leading and participating on delivery teams likely would fail or lead to ineffective implementation, which is another reason why a more thoughtful and deliberate approach to the change is required.

What does this have to do with culture? Well, architecture is fundamentally about solution quality in technology, reuse, managing complexity and cost of ownership, and enabling speed and disciplined innovation. Establishing roles with an accountability for quality will test the appetite within an organization when it comes to working beyond individual project goals and constraints to looking at more strategic objectives for simplification, speed, and reuse. Where courageous leadership and the right culture are not in place, evolving the IT operating model will be considerably more difficult, likely at every stage of the process.

Manage Reality

To this point, I’ve addressed change in a fairly uniform and somewhat idealistic manner, but reality is often quite different, so I wanted to explore a couple situations and how I think about the implications of each.

Non-Uniform Execution

So, what happens when you change culture within your team, but it doesn’t extend into those who work directly with you? It depends on the nature of the change itself, of course, but likely the farther “out” from center you go, the more difficult it will be for your team to capitalize on whatever the intended benefits of the change were intended to be.

My assumptions here are in relation to medium- to larger-scale organizations, where the effects are magnified and it is impractical to “be everywhere, all the time” to engage in ways that help facilitate the desired change.

In the case that there isn’t broader alignment to whatever cultural adjustments you want to make within your team, depending on the degree of difference to the broader company culture, it may be necessary to clarify how “we operate internally” versus how “we engage with others”. The goal of drawing out that separation would be to try and drive performance improvement within your team, but not waste energy and create friction in your external interactions.

There is a potential risk in having teams with a very different culture than the broader organization if it creates an environment where there becomes an “us and them” mentality or a special treatment situation where that team demonstrates unhealthy organizational behaviors or is held to different standards than others. Ultimately those situations cause larger issues and should be avoided where possible.

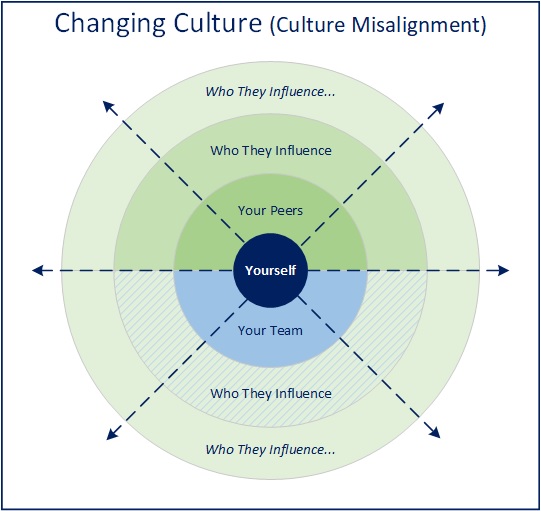

Handling Disparate Cultures

Unlike the previous situation where there is one broader culture and a team operates in a slightly different manner; I’ve also seen situations where groups operate with very different cultures within the same overall organization and it can create substantial disconnects if not addressed effectively. When not addressed there can be a lot of internal friction, competition, and a lack of effective collaboration, which will hinder performance in one or more ways over time.

One way to manage a situation where there are multiple distinct cultures within a single organization, would first be to look for some level of core, universally accepted operating principles that can be applied to everyone, but then to focus entirely on the points of engagement across organizations, clarify roles and responsibilities for each constituent group, and manage to those dependencies the same as you would if working with a third-party provider or partner. The overall operating performance opportunity may not be fully realized, but this kind of approach could be used to provide clarity of expectations and reduce friction points to a large degree.

Wrapping Up

The purpose of this article was to come back to a core element that makes organizations successful over time, and that’s culture. To the degree that there are gaps or issues, it is always possible to adapt and evolve, but it takes a thoughtful approach, the right leadership, and time to make sustainable change. In my opinion, it is time worth spending to the degree that performance and excellence is your goal. It will never be “perfect” for many reasons, but thinking about how you establish, reinforce, and evolve it in a disciplined way can be the difference to remaining agile, competitive, and successful overall.

I hope the ideas were worth considering. Thanks for spending the time to read them. Feedback is welcome as always.

-CJG 10/03/2025