Overview

Having touched on the importance of quality in accelerating value in my latest article Creating Value Through Strategy, I wanted to dive a little deeper into the topic of “speed versus quality”.

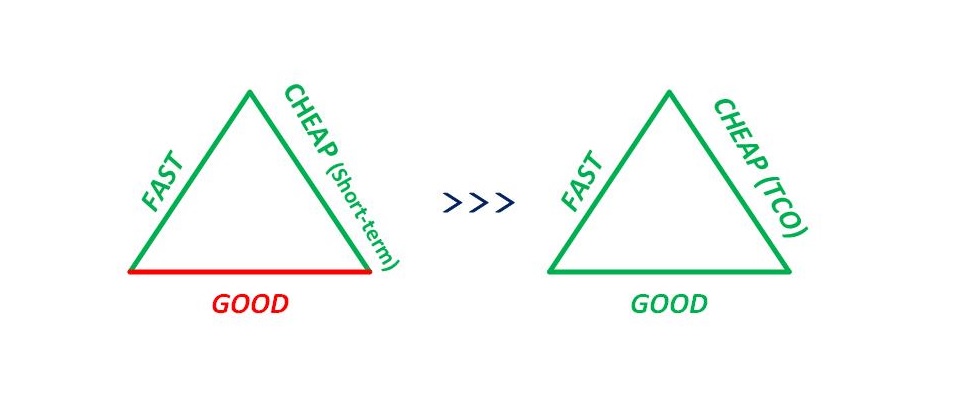

For those who may be unfamiliar, there is a general concept in project delivery that the three primary dimensions against which you operate are good (the level of effort you put into ensuring a product is well architected and meets functional and non-functional requirements at the time of delivery), fast (how quickly or often you produce results), and cheap (your ability to deliver the product/solution at a reasonable cost).

The general assumption is that the realities of delivery lead you to having to prioritize two of the three (e.g., you can deliver a really good product fast, but it won’t be cheap; or you can deliver a really good product at a low cost, but it will take a lot of time [therefore not be “fast”]). What this translates to, in my experience, has nearly always been that speed and cost are prioritized highest, with quality being the item compromised.

Where this becomes an issue is in the nature of the tradeoff that was made and the longer-term implications of those decisions. Quality matters. My assertion is that, where quality is compromised, “cheap” is only true in the short-term and definitely not the case overall.

The remainder of this article will explore several dimensions to consider when making these decisions. This isn’t to say that there aren’t cases where there is a “good enough” level of quality to deliver a meaningful or value-added product or service. My experience, however, has historically been that the concepts like “we didn’t have the time” or “we want to launch and learn” are often used as a substitute for discipline in delivery and ultimately undermine business value creation.

Putting Things in Perspective

Dimensions That Matter

I included the diagram above to put how I think of product delivery into perspective. In the prioritization of good, fast, and cheap, what often occurs is that too much focus and energy goes into the time spent getting a new capability or solution to market, but not enough on what happens once it is there and the implications of that. The remainder of this section will explore aspects of that worth considering in the overall context of product/solution development.

Some areas to consider in how a product is designed and delivered:

- Architecture

- Is the design of the solution modular and component- or service-based? This is important to the degree that capabilities may emerge over time that surpass what was originally delivered and, in a best-of-breed environment, you would ideally like to be able to replace part of a solution without having to fundamentally rearchitect or materially refactor the overall solution

- Does the solution conform to enterprise standards and guidelines? I’ve seen multiple situations where concurrent, large-scale efforts were designed and developed without consideration for their interoperability and adherence to “enterprise” standards. By comparison, developing on a “program-“ or “project-level”, or in working with a monolithic technology/solution (e.g., with a relatively closed ERP system), creates technology silos that lead to a massive amount of technical debt as it is almost never the case that there is leadership appetite for refactoring or rewriting core aspects of those solutions over time

- Is the solution cloud-native and does it support containerization to enable deployment of workloads across public and private clouds as well as the edge? In the highly complex computing environments of today, especially in industries like Manufacturing, the ability to operate and distribute solutions to optimize availability, performance, and security (at a minimum) is critical. Where these dimensions aren’t taken into account, there would likely be almost an immediate need for modernization to offset the risk of technology obsolescence at some point in the next year or two

- Security

- Does the product or service leverage enterprise technologies and security standards? Managing vulnerabilities and migrating towards “zero trust” is a critical aspect of today’s technology environment, especially to the degree that workloads are deployed on the public cloud. Where CI/CD pipelines are developed as part of a standard cloud platform strategy with integrated security tooling, the enterprise level ability to manage, monitor, and mitigate security risk will be significant improved

- Integration

- Does the product or service leverage enterprise technologies and integration standards? Interoperability with other internal and external systems, as well as your ability to introduce and leverage new capabilities and rationalize redundant solutions over time is fundamentally dependent on the manner in which applications are architected, designed, and integrated with the rest of a technology footprint. Having worked in environments with well-defined standards and strictly enforced governance versus ones where neither were in place, the level of associated complexity and costs in the ultimate operating environments was materially different

- Data Standards

- Does the product or service align to overall master data requirements for the organization? Master data management can be a significant challenge from a data governance standpoint, which is why giving this consideration up front in a product development lifecycle is extremely important. Where it isn’t considered in design, the end result could be master data that doesn’t map or align to other hierarchies in place, complicating integration and analytics intended to work across solutions and the “cleanup” required of data stewards (to the degree that they are in place) could be expensive and difficult post-deployment

- Are advanced analytics aspirations taken into account in the design process itself? This is an area becoming increasingly important given AI-enabled (“intelligent”) applications as discussed in my article on The Intelligent Enterprise. Designing with data standards in mind and an eye towards how it will be used to enable and drive analytics, likely in concert with data in other adjacent or downstream systems is a step that can save considerable effort and cost downstream when properly addressed early in the product development cycle

- “Good Enough”/Responsive Architecture

- All the above points noted, I believe architecture needs to be appropriate to the nature of the solution being delivered. Having worked in environments where architecture standards were very “ivory tower”/theoretical in nature and made delivery extremely complex and costly versus ones where architecture was ignored and the delivery environment was essentially run with an “ask for forgiveness” or cowboy/superhero mentality, the ideal state in my mind should be somewhere in between, where architecture is appropriate to the delivery circumstances, but also mindful of longer-term implications of the solution being delivered so as to minimize technical debt and further interoperability in a connected enterprise ecosystem environment.

Thinking Total Cost of Ownership

What makes product/software development challenging is the level of unknowns that exist. At any given time, when estimating a new endeavor, you have the known, the known unknown, and the complete unknown (because what you’re doing is outside your team’s collective experience). The first two components can be incorporated into an estimation model that can be used for planning and the third component can be covered through some form of “contingency” load that is added to an estimate to account for those blind spots to a degree.

Where things get complicated is, once execution begins, the desire to meet delivery commitments (and the associated pressure thereof) can influence decisions being made on an ongoing basis. This is complicated by the normal number of surprises that occur during any delivery effort of reasonable scale and complexity (things don’t work as expected, decisions or deliverables are delayed, requirements become increasingly clear over time, etc.). The question is whether a project has both disciplined, courageous leadership in place and the appropriate level of governance to make sure that, as decisions need to made in the interest of arbitrating quality, cost, time, and scope, that they are done with total cost of ownership in mind.

As an example, there was a point in the past where I encountered a large implementation program ($100MM+ in scale) with a timeline of over a year to deploy an initial release. During the project, the team announced that all the pivotal architecture decisions needed to be made within a one-week window of time, suggesting that the “dates wouldn’t be met” if that wasn’t done. That logic was then used at a later point to decide that standards shouldn’t be followed for other key aspects of the implementation in the interest of “meeting delivery commitments”. What was unfortunate in this situation was that, not only were good architecture and standards not implemented, the project encountered technical challenges (likely due to one or two of those root causes, among other things) that caused it to be delivered over a year late regardless. The resulting solution was more difficult to maintain, integrate, scale, or leverage for future business needs. In retrospect, was any “speed” obtained through that decision making process and the lack of quality in the solution? Certainly not, and this situation unfortunately isn’t unique to larger scale implementations in my experience. In these cases, the ongoing run rate of the program itself can become an excuse to make tactical decisions that ultimately create a very costly and complex solution to manage and maintain in the production environment, none of which anyone typically wants to remediate or rewrite post-deployment.

So, given the above example, the argument could be made that the decisions were a result of inexperience or pure unknowns that existed when the work was estimated and planned to begin with, which is a fair point. Two questions come to mind in terms of addressing this situation:

- Are ongoing changes being reviewed through a change control process in relation to project cost, scope, and deadline, or are the longer-term implications in terms of technical debt and operating cost of ownership also considered? Compromise is a reality of software delivery and there isn’t a “perfect world” situation pretty much ever in my experience. That being said, these choices should be conscious ones, made with full transparency and in a thoughtful manner, which is often not the case, especially when the pressures surrounding a project are high to begin with.

- Are the “learnings” obtained on an ongoing basis factored into the estimation and planning process so as to mitigate future needs to compromise quality when issues arise? Having been part of and worked closely with large programs over many years, there isn’t a roadmap that ever plays out in practice how it is drawn up on paper at the outset. That being said, every time the roadmap is revised, as pivot points in the implementation are reached and plans adjusted, are learnings being incorporated such that mistakes or sacrifices to quality aren’t being repeated over and over again. This is a tangible thing that can be monitored and governed over time. In the case of Agile-driven efforts, it would be as simple as looking for patterns in the retrospectives (post-sprint) to see whether the process is improving or repeating the same mistakes (a very correctible situation with disciplined delivery leadership)

Speed on the Micro- Versus Macro-Scale

I touched on this somewhat in the previous point, but the point to call out here is that tactical decisions made in the interest of compromising quality for the “upcoming release” can and often do create technical issues that will ultimately make downstream delivery more difficult (i.e., slower and more costly).

As an example, there was a situation in the past where a team integrated technology from multiple vendors that provided the same underlying capability (i.e., the sourcing strategy didn’t have a “preferred provider”, so multiple buys were done over time using different partners, sometimes in parallel). In each case, the desire from the team was to deliver solutions as rapidly as possible in the interest of “meeting customer demand” and they were recognized and rewarded for doing so at speed. The problem with this situation was that the team perceived standards as an impediment to the delivery process and, therefore, either didn’t leverage any or did so on a transactional or project-level basis. Where this became problematic was where there became a need to:

- Replace a given vendor – other partners couldn’t be leveraged because they weren’t integrated in a common way

- Integrate across partners – the technology stack was different and defined unique to each use case

- Run analytics across solutions – data standards weren’t in place so that underlying data structures were in a common format

The point of sharing the example is that, at a micro-level, the team’s approach seems fast, cheap, and appropriate. The accumulation of the technical debt, however, is substantial when you scale and operate under that mindset for an extended period of time, and it does both limit your ability to leverage those investments, migrate to new solutions, introduce new capabilities quickly and effectively, and integrate across individual point solutions where needed. Some form of balance should be in place to optimize the value created and cost of ownership over time. Without it, the technical debt will undermine the business value in time.

Consulting Versus Corporate Environments

Having worked in both corporate and consulting environments, it’s interesting to me that there can be a different perspective on quality depending on where you sit (and the level of governance in place) in relation to the overall delivery.

Generally speaking, it’s somewhat common on the corporate side of the equation to believe that consultants lack the knowledge of your systems and business to deliver solutions you could yourself “if you had the time”. By contrast, on the consulting side, ideally, you believe that clients are thinking of you as a “hired gun” when it comes to implementations, because you’re bringing in necessary skills and capacity to deliver on something they may not have the experience or bench strength to deliver on their own.

So, with both sides thinking they know more than the other and believing they are capable of doing a quality job (no one does a poor job on purpose), why is quality so often left unattended on larger scale efforts?

On this point:

- The delivery pressures and unknowns I mentioned above apply regardless of who is executing a project.

- A successful delivery in many cases requires a blend of internal and external resources (to the extent they are being leveraged) so there is a balance of internal knowledge and outside expertise to deliver the best possible solution from an objective standpoint.

- Finally, you can’t deliver to standards of excellence that aren’t set. I’ve seen and worked in environments (both as a “client” and as a consultant) where there were very exacting standards and expectations of quality and ones where quality wasn’t governed at the level it should be

I didn’t want to belabor this aspect of delivery, but it is interesting how the perspective and influence over quality decisions can be different depending on one’s role in the delivery process (client, consultant, or otherwise).

Wrapping Up

Bringing things back to the overall level, the point of writing this article was to provide some food for thought on the good, fast, cheap concept and the reality that, in larger and more complex delivery situations, the cost of speed isn’t always evaluated effectively. There is no “perfect world”, for certain, but having discipline, thinking through some of the dimensions above, and making sure the tradeoffs made are thoughtful and transparent in nature could help improve value/cost delivered over time.

I hope the ideas were worth considering. Thanks for spending the time to read them. Feedback is welcome as always.

-CJG 12/10/2023

6 thoughts on “Fast and Cheap, Isn’t Good…”